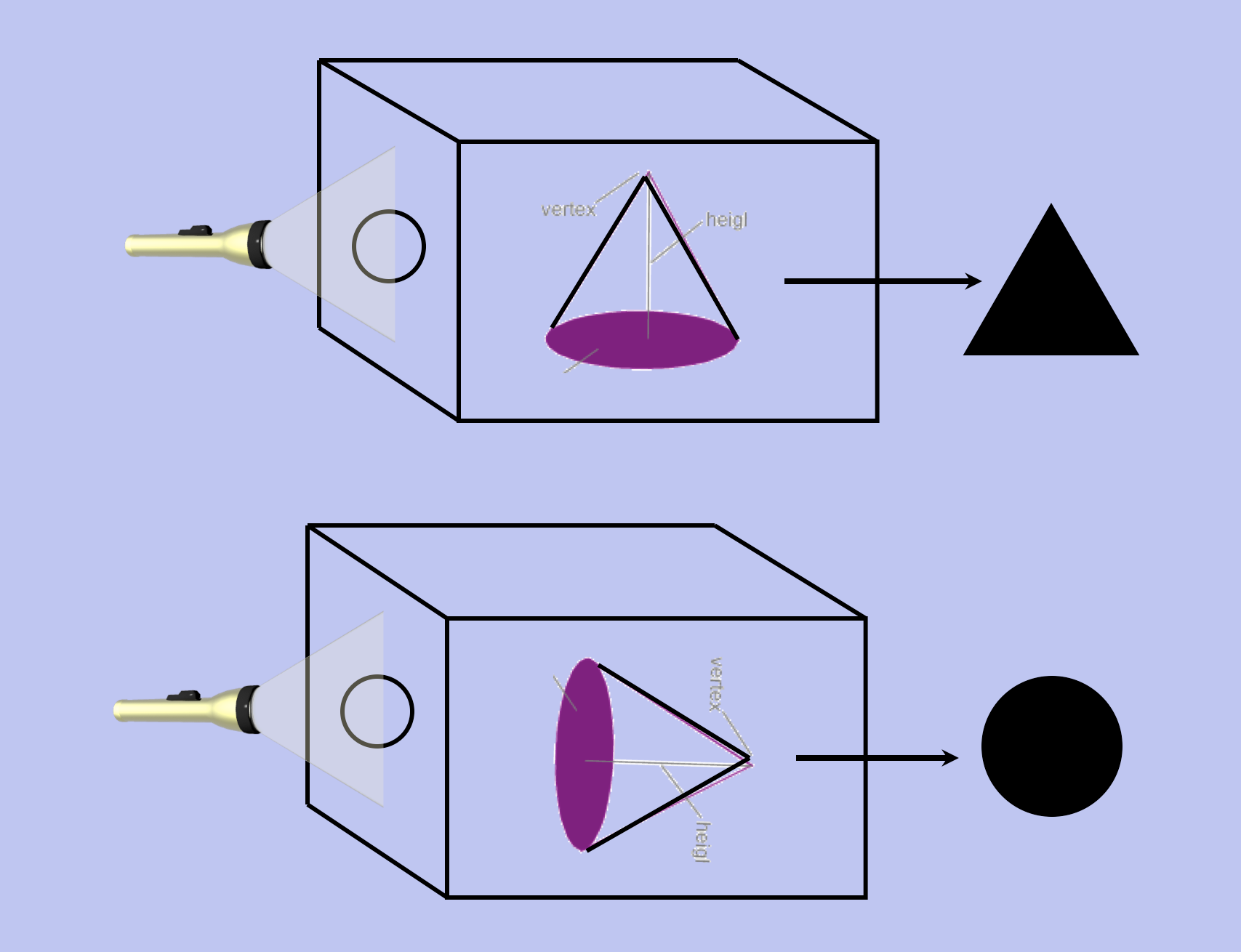

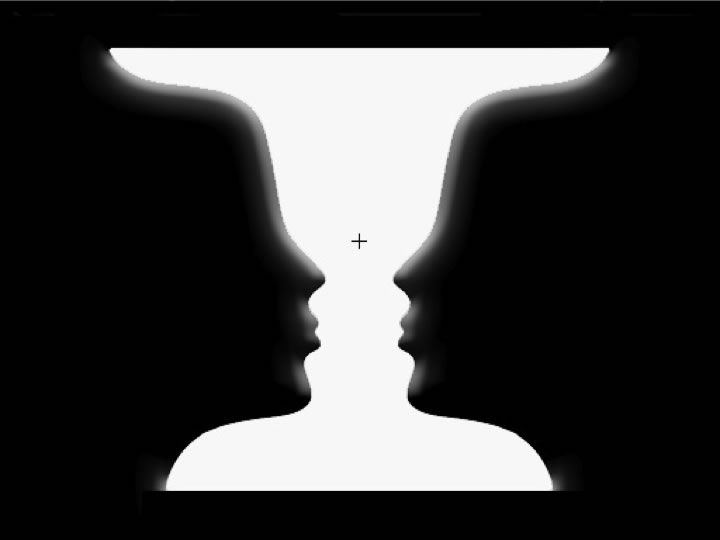

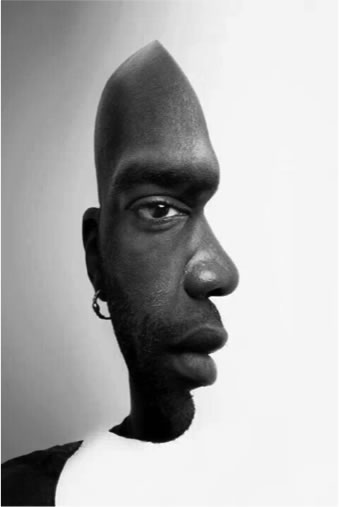

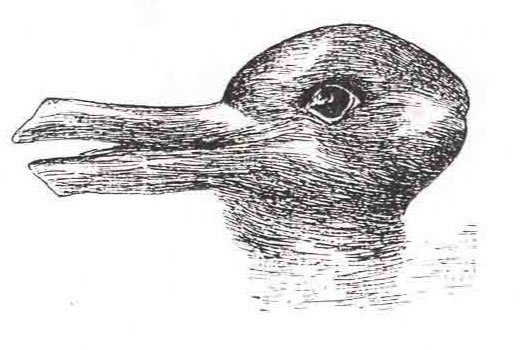

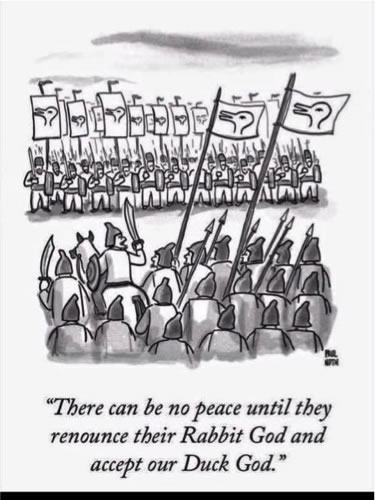

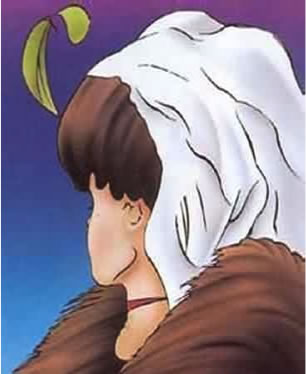

But let me offer another example of how seeing can be deceiving, one that is clearly of sociological interest and has important policy implications: poverty. We will cover this in greater detail later in the semester.

According to some political commentators whose political perspective leans to the right – as well as to some ordinary citizens – America has a permanent underclass of unproductive citizens who prefer to live on welfare and other means of government support. These people, the argument goes, do not take personal responsibility for their situation and they are unwilling to make the effort to lift themselves up out of their circumstances. They remain in poverty by choice.

Moreover, the argument continues, federal spending on entitlements and other programs - such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) - that provide cash benefits, for the most part, are promoting laziness and creating a dependent class of Americans who would rather collect government benefits than find a job. And since their children receive little educational encouragement at home they become stuck in a cultural setting that destroys their work ethic and they grow up to be copies of their parents thereby perpetuating the existence of this underclass.

Unfortunately, such people do exist in the United States and recent estimates are that they number between five and six million of our citizens. They are unquestionably the toughest challenge for policymakers because almost nothing about their lives equips them to escape from poverty and the circumstances that surround them.

And these people are visible –we see them on the street corners in inner cities and on the news. And it seems to many that these people – often refereed to as “the disreputable and undeserving poor” – are just “working the system” and taking our hard earned tax dollars through government hand-outs. They lack the “character” to work hard and improve their situation – and why should they try to improve if they can live off our tax dollars with little effort? So, why should we help them?

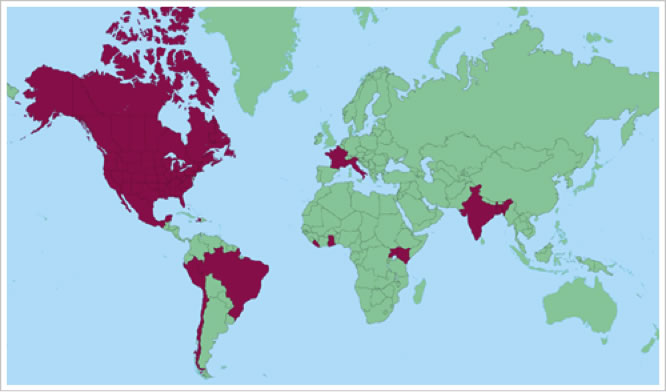

If these 6 million were representative of those living beneath the poverty line in the United States, I might take this argument seriously. But (as of 2018) there are roughly 38 million people United States that live in poverty - 11.8 percent of the population. And we don't see them or either recognize or acknowledge their existance.

So we have to ask: does the visibility of the six million deceive us into thinking that the other 32 million are just like them?

Or is it possible – perhaps even likely – that the reason we don’t see the "other 32 million living under the poverty line is because they are working either full-time or hold 2 or more part time jobs trying to stay afloat? Could it be that many folks living below the poverty line are hard-working, reputable people – that being poor is less a matter of “character” and more a question of access to resources? Of wages?

The Disreputable and Undeserving Poor

But it's not the 32 million that come to mind when thinking about the poor, it's the 6 million, the more visible segment of the poor population – the “disreputable and undeserving poor.”

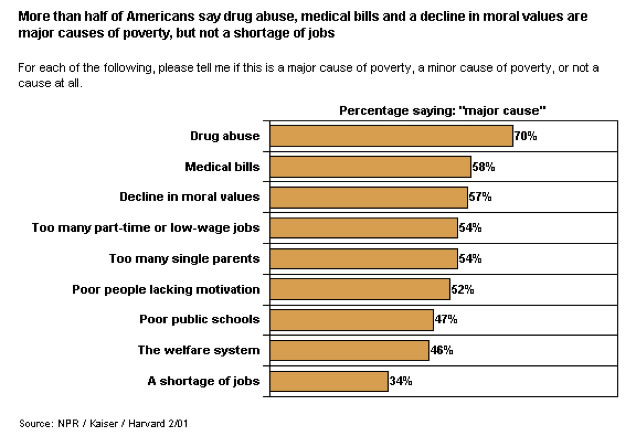

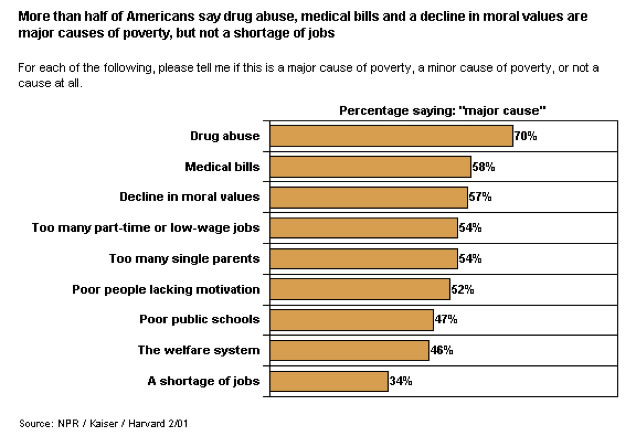

Perhaps this is why, when asked what, in their opinion, were major causes of poverty, more than half of those surveyed answered “a decline in moral values” and “poor people’s lack of motivation.” The emphasis on "individual characteristics," as shall be seen, deflects our attention away from the larger societal context. And who do you think came to mind when the respondents were answering these questions? The 6 million or the other 32 million?

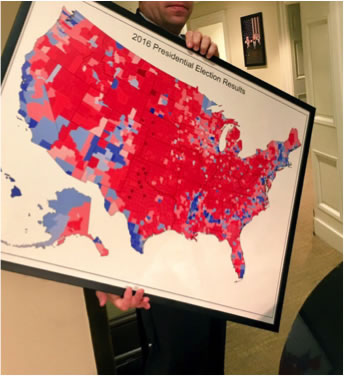

More recent research has uncovered - as you might suppose - a partisan divide: When asked why a person is poor, 12% of those identiying with or leaning toward the Democrat party said that in their view poor people have not worked as hard as most other people. For those identifying with or leaning toward the Republican Party, 42% shared this view.

There are many different pathways to poverty and, of course, some involve the personal shortcomings and poor choices of individuals. There are those 6 million visible poor people in the U.S. But there are also the other 32 million – and given the COVID-19 pandemic and the 36 million who have just lost their jobs and health insurance, the numbers are certainly rising.

Nevertheless, thinking that the 6 million so-called disreputable poor are in fact representative of all those living below the poverty line has serious consequences. The attitudes toward the poor – the ways in which the working poor are perceived – certainly need improvement. Just consider McDonald’s recent interaction with its workers.

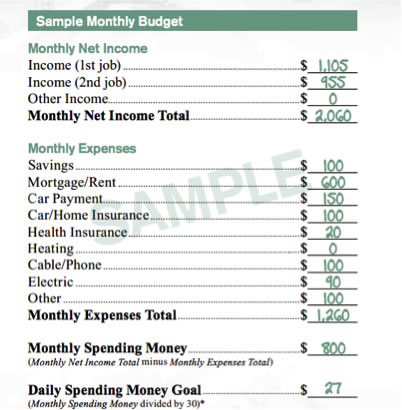

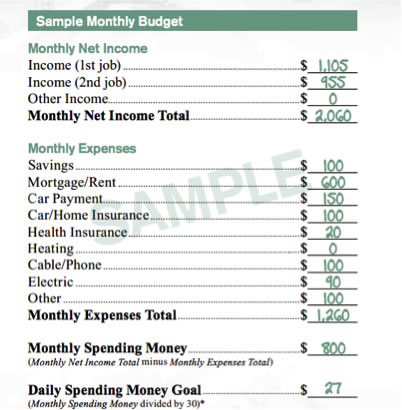

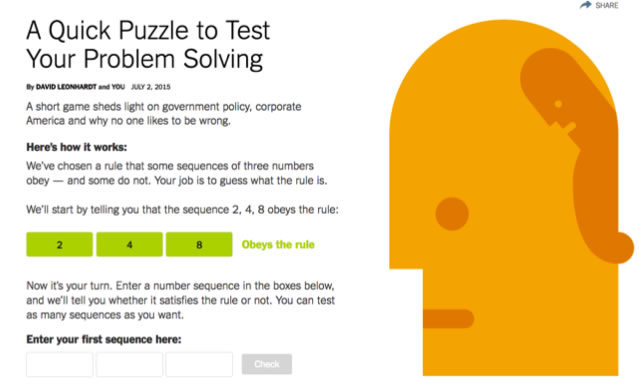

When workers at McDonald's organized a work-stoppage and demanded a $15 hourly wage, rather that acknowledging even the slightest legitimacy of the dispute, the company chose to "educate" workers to live on the salary they earned. They printed a glossy pamphlet, complete with a "Sample Monthly Budget" to show its workers that they could even save money each month if they simply lived within their means. The sample budget is below - and before you look carefully at the recommended monthly expenses - asking yourself whether or not they are reasonable - look at the top where it lists your monthly net income and notice that in order to approach the monthly net income of $2,060 - which barely gets you above the poverty line for a family of three - YOU MUST WORK TWO JOBS: the first at McDonald's for 40 hours a week, the second job (presumably of your choice) for another 35 hours a week!

Is this a respectful attitude toward their workers?

And then, perhaps because one has the stereotypical "disreputable and undeserving" poor in mind, more than a few people believe that those getting public support are "living easy." You have probably heard the outlandish statement that having more children will raise your benefits to the extent that you actually make a profit! Although this misconception can be easily checked and refuted, somehow it perseveres.

So here are the numbers, put out by the government, for poor people in Texas who receive "Temporary Assistance to Needy Families" (TANF) - this used to be the section in welfare devoted to "Aid to Families with Dependent Children" - and the "Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program" (SNAP) - which was once called "Food Stamps." This year, 2020, a family of three, with no reported income, will receive a maximum of $303 each month from TANF and $509 each month from SNAP..The monthly total is $812. Restrictions apply and recipients must be seeking employment or be in an approved work program. If the recipient received a full year's benefits, it would amount to $9,744 for the year. Since the poverty line for a family of three in 2020 is $21,720, these benefits will be 45% - less than one-half – of what the government considers to be the necessary amount of money a family of three needs to subsist. Put aside the SNAP food allowance and you are looking to pay rent and all other expenses from the $303 TANF funds (which Texas has consistently kept at 17% of the federal poverty line). Is this what "easy liivng" looks like?

"Getting Something for Nothing"

But still . . . you might agree that the benefits don't go very far . . . but at least it's something. But you work hard for your money and could also use a little help but don't get anything while they are getting something for nothing! An interestin gthought that deserves attention.

Of course, a majority of the people collecting these benefits have paid into the system when they were working, just as you might be doing now (remember we’re not mistaking the disreputable poor for all of those receiving benefits).

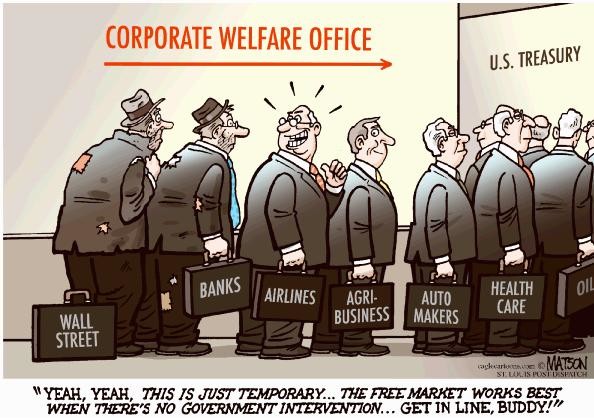

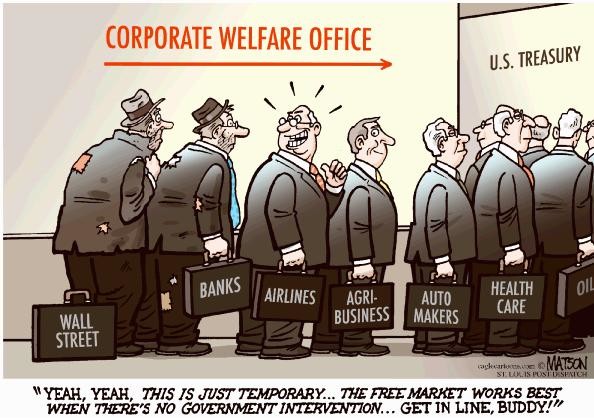

But who else gets money from the government – what some economists refer to as entitlements? Remember the Burke Theorem: A way of seeing is also a way of not seeing.

Let's say that you are buying a house. As you know, the way things are set up, homeowners can claim the interest that they pay on their home loan as a tax deduction each year until the loan is paid off. And a larger tax deduction means a larger tax refund from the government. So, look at this table with data from this year – 2020. Interest rates are fairly low at 4%, and let’s assume that you are well-off financially and in an upper tax bracket – say, 30%.

You can see the loan amount in the left column, the amount of interest paid the first year of the mortgage (it gets reduced little by little over the course of paying off the loan) in the center column, and the amount of money the taxes you owe are reduced in the right column. And let's remember that the family of three in Texas is receiving $9,744 in benefits from the government.

Amount of Loan |

Interest Payment |

Tax Rebate |

$ 250,000 |

$ 10,000 |

$ 3,000 |

$ 500,000 |

$ 20,000 |

$ 6,000 |

$ 750,000 |

$ 30,000 |

$ 9,000 |

$1, 000,000 |

$ 40,000 |

$12,000 |

$2,000,000 |

$ 80,000 |

$24,000

|

$3,000,000 |

$120,000 |

$36,000 |

$4,000,000 |

$160,000 |

$48,000 |

$5,000,000 |

$200,000 |

$60,000 |

So let’s say that you bought a house for $1,00,000 and your down payment was the standard 25%, or $250,000. And having that kind of money available – and being in the 30% tax-bracket – is a clear indication that you are quite affluent. The amount of your loan, then, would be $750,000. You would be paying $30,000 in interest that first year, which would reduce your tax burden by $9,000. That is to say that the government is giving you, an affluent person, $9,000 – nearly as much as that family of three on TANF and SNAP – for what? And the more expensive your house – and the larger the amount of your loan – the more money stays in your pocket. What have you done to deserve this government handout? Aren’t homeowners also getting something for nothing?

Now, you might come up with all sorts of arguments, like:

“I worked hard for my money, I’m a good citizen, and I deserve to be rewarded

Yes, you did work hard and you did a good job. But you were paid rather handsomely to do so. You already got was coming to you. Why should you get the added bonus and given money because you spent money? Isn’t the nice house enough? Renters don’t get a tax break for the rent they pay . . .

“I already pay my fair share of taxes – more than most because I make a good salary – and this was my money to begin with.”

Yes, that’s true. It’s everybody’s money to begin with – then the tax laws dictate that we hand a certain percentage back to the government. If you disagree, make an effort to get the laws changed.

And by living in a nice neighborhood, you get more and quicker service than most others . . .

“By buying this house I am contributing to the economy and creating jobs.”

Everyone that buys something contributes to the economy without getting a tax rebate for doing so. Do you get – or should you get – a tax break for buying a car? A big screen television? A boat?

And let’s be honest – if your tax deduction for interest payments on a house was rescinded, you would still buy a house – creating the same number of jobs – but perhaps a slightly less expensive one.

But the facts remain: wealthy people – and, of course, corporations – get far more in government “entitlements” than the poor.

The amount of money the government "gives" to the wealthy and corporations far outstripes the amount that it spends on entitlement programs - by far . . .

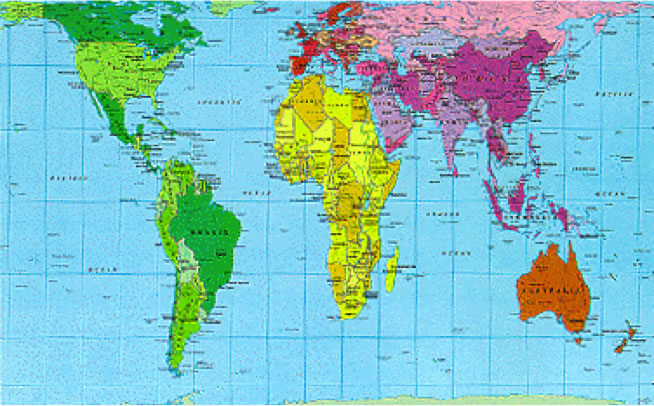

I started off this section on “seeing can be deceiving” with reference to poverty by arguing that the visible poor – the one’s that many consider to be disreputable and undeserving of our help – are not representative of those living below the poverty line. So how should we think about these “other” poor?

Much attention will paid to this in Unit 7. For the moment, I would like to simply state that rather than focusing upon the individual characteristics of this or that person, we should shift our perspective and examine the structure of opportunities for the poor in contemporary society and their access to opportunities.

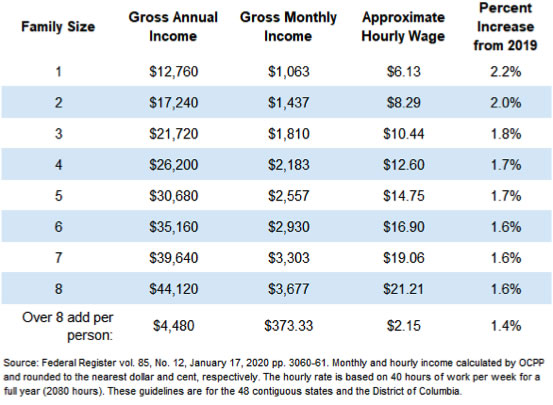

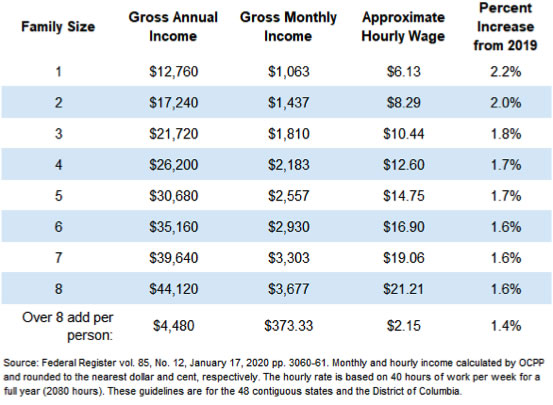

Why can't the 32 million "other" people pull themselves up? Consider, first, the Federal Poverty Guidelines for 2020 listed below.

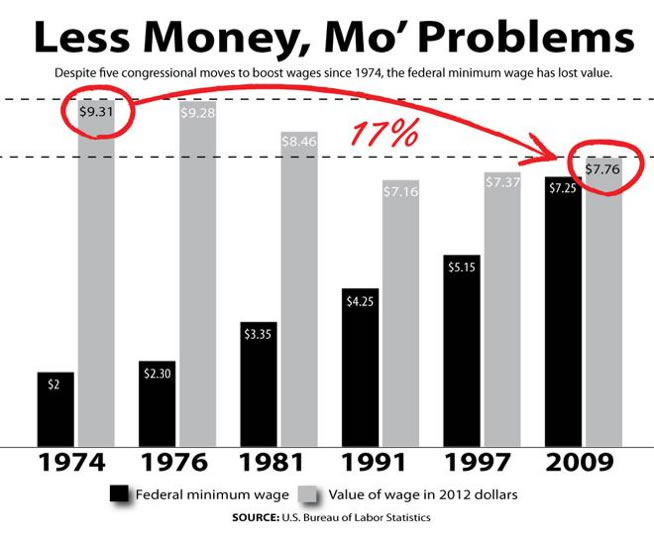

As you can see, the federal minimum hourly wage - which is $7.25 - will get an individual (barely) above the poverty line, but not a family of two or more.

Entry level factory positions in the U.S. start at $18,525 per year. The average factory worker salary is $25,350 which still doesn't reach the poverty line for a family of four.

The poverty guidelines were originally designed to reflect the minimum amount of income that American households need to subsist. In the early 1960s, this amount was derived by multiplying by three the cost of food for each family size and this remains the same today, despite significant shifts in household expenses.

For example, the cost of housing as a share of household income has increased significantly since the 1960s, and families today are more likely to have child-care expenses and pay a much higher share of health care costs than was typical in the 1960s. Except in the case of Alaska and Hawaii, the guidelines do not take into account geographical differences in the cost of living, or the effects of a rising standard of living.

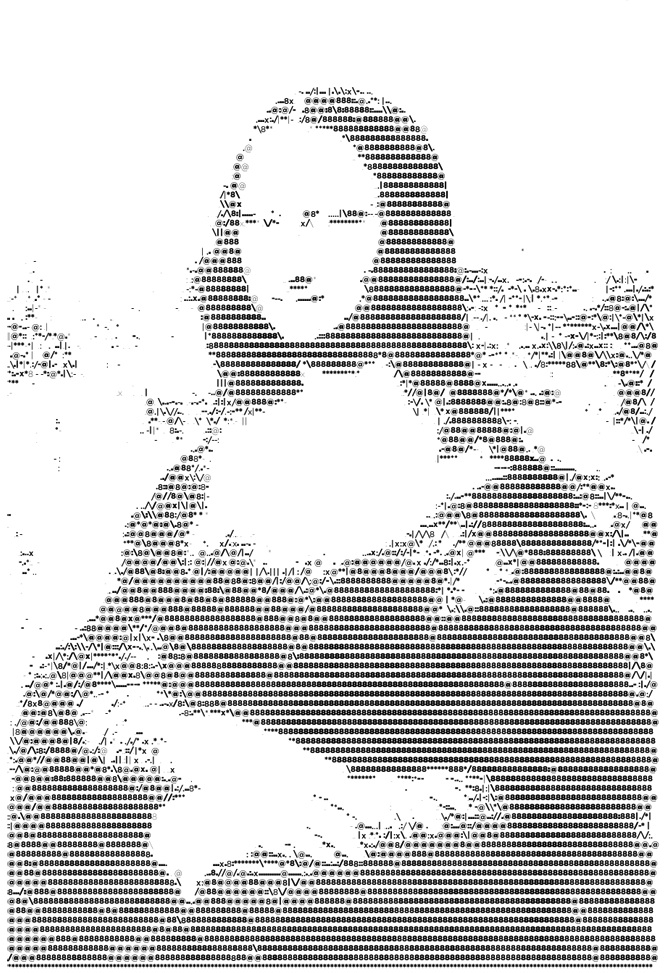

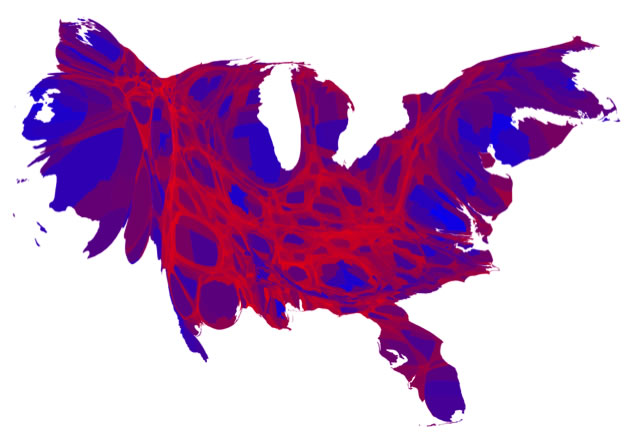

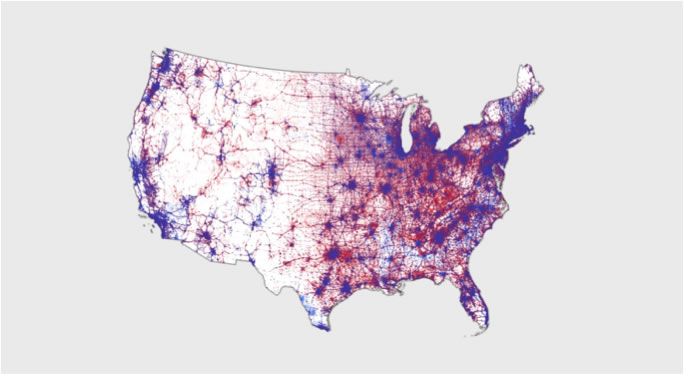

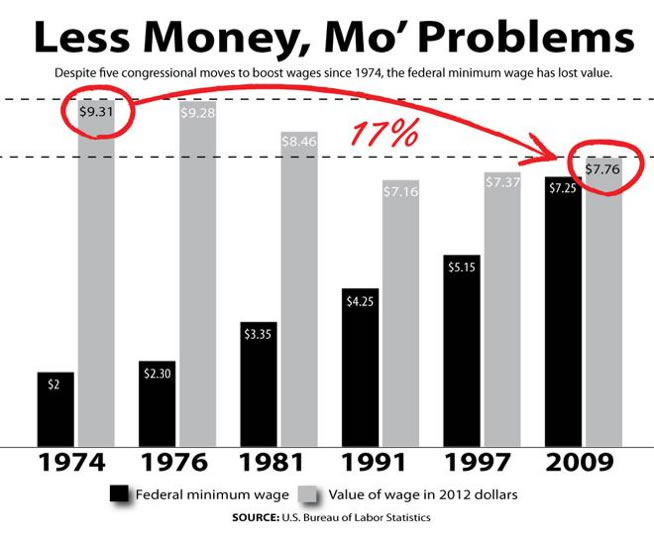

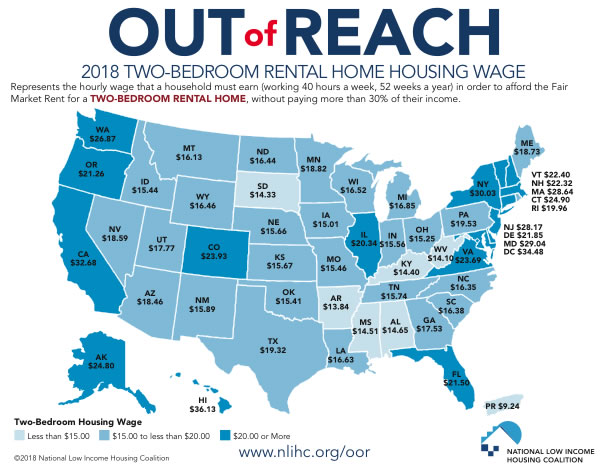

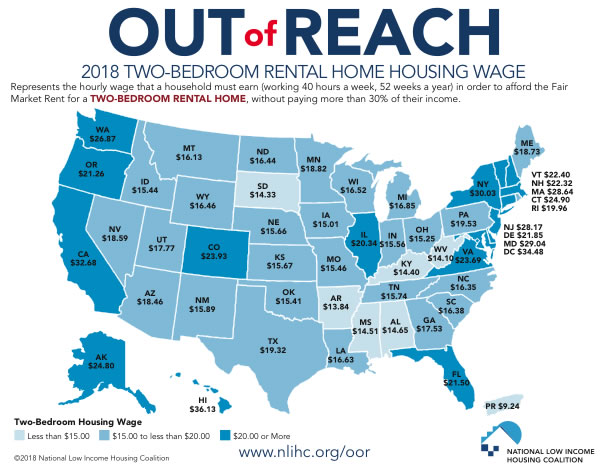

And as can be seen, today's minimum wage of $7.25 has less purchasing power than the $2.00 wage in 1974. And here, below, is a map of the U.S. indicating how much an hourly wage it would take to afford the fair market value of renting a two-bedroom apartment.

S

S