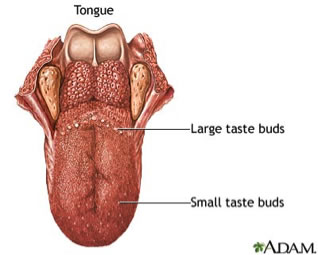

All kisses, of course, are not alike. They have different functions. It can be a simple greeting. There are kisses of joy, of love and endearment, of passion and lust, of commitment and comfort, of social grace and necessity, of sorrow and supplication.

The Romans, in fact, created a typology of kisses, with Osculum referring to a social or friendship kiss, or kiss out of respect, Basium, which referred to an affectionate kiss for family members, and Savium, which was a sexual or erotic kiss.

To indicate its importance in German culture, we find that the German language has words for 30 different kinds of kisses, including nachküssen, which is defined as a kiss "making up for kisses that have been omitted.”

And if we were to trace the kiss through history, we would find that an individual’s social standing determined where to kiss another person in greeting. Kisses moved from the lips downward as kissers moved down the social hierarchy.

Kissing feet, for example, was customary throughout the Middle Ages.

A Kiss was a sign of trust between feudal lords and vassals.

A Kiss was a legal way to seal contracts (“sealed with a kiss”)

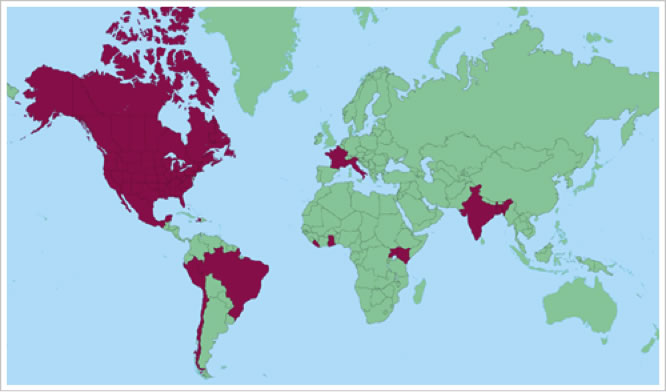

There are also fundamental cultural differences among industrialized nations. In Finland, people tend to be more private and rarely kiss in public. In Japan, since kissing is associated more with sex, a public display is considered inappropriate – even vulgar. In the United Kingdom, people are more likely to shake hands.

Although the “French kiss” entered the English vocabulary in 1923, according to Alfred Kinsey, kissing style was found to correlate with a person’s level of education. Seventy percent of well-educated men admitted to French kissing, while only 40 percent of those who dropped out of high school did.

Still, judging from a quick look at popular culture, Americans appear to be rather interested in kissing. |

S

S