And how is one’s feeblemindedness to be determined? By looking at their score on an IQ test which, at the time, was clearly inadequate.

Such sterilizations no longer occur today. But the ideas underpinning those procedures – that some people, by their nature, are less capable than others – still persists. You can hear echoes of these ideas in current immigration debates, as well as the controversy over whether intelligence is genetically determined and whether significant immutable – resistant to change – differences exist between the two sexes and between different racial categories. And, with new advances in genetics and biotechnology, some say that a new “backdoor eugenics” has emerged.

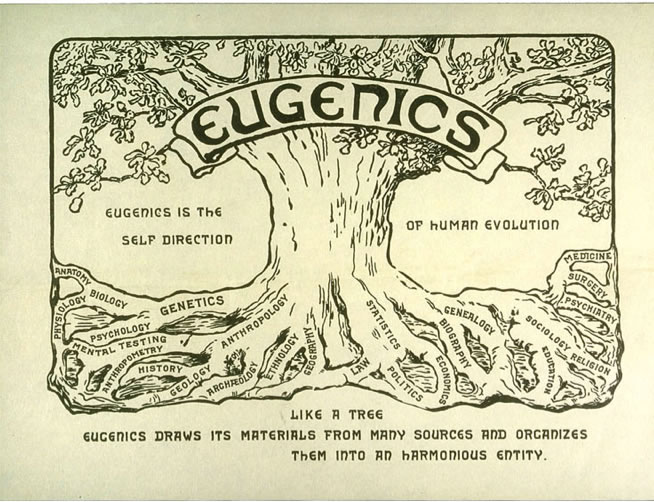

If you enter “eugenics” into google, you will get two-and-a-half million hits. One web page, titled “Future Generations,” is allegedly devoted to “humanitarian eugenics.”

So the answer, a human being is, for the most part, their genetic endowment – at that their biology trumps other factors in explaining what they do and how they do it, has policy consequences.

If you believe that a category of people are by their very nature less intelligent than others, and, as a result, are more apt to make poor decisions in life – ie., act promiscuously, commit crimes, or act in such a way that leads them into poverty – then you will likely advocate quite different laws and social policies than someone who places greater emphasis on environmental factors. If you believe that “orange” people are, by their very nature less intelligent than others then, when confronted with the fact that they are less likely to be doctors or engineers or physicists you would likely say, “What would you expect? You need to be smart to be in those professions and they are less so than others.” You wouldn’t consider that there were other factors involved – that, perhaps, purple people were not afforded the same opportunities as others, or that their local neighborhood schools were inadequate. This matters. |