Sociology 1301

Introduction to Sociology

Collin College

Professor Larry Stern

What is Sociology?

|

Sociology 1301

|

|

Who are these People that become Sociologists? |

|

| So, what is sociology and who are these people who say that they are sociologists? |

Anthony Giddens 1938 - |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

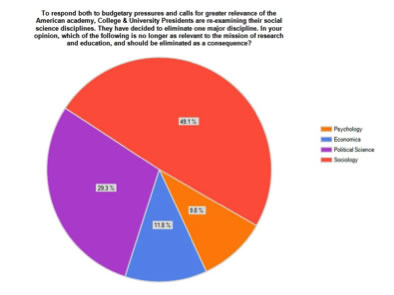

Social Activism vs. Scientific Objectivity? |

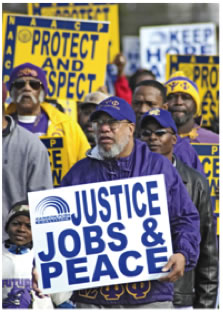

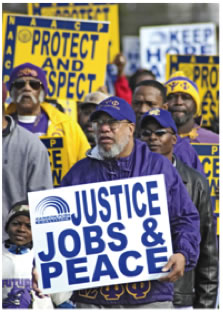

Leaving all of this aside, I think that it is important that you know that from its birth, the discipline of sociology has been marked by a fundamental dilemma and tension that has sparked serious debate time and again throughout its one hundred twenty-five year history. On the one side are those sociologists who exhibit a critical stance toward existing social arrangements, seek to pinpoint the causes and consequences of social problems, and offer remedies they believe would reduce the extent to which these problems exist. They typically share a commitment to greater social equality and the collective use of reason to create a better and more just social world. |

Karl Marx 1818 - 1883 |

|

William Ogburn 1886 - 1959 |

|

Robert E. Park 1864 - 1944 |

|

Although advocates of each of these two positions coexist side-by-side at any one time, the prominence of one or the other of these positions changes over time, swinging like a pendulum back and forth between these two extremes. Let me give just one example, drawn from the early years in sociology’s development. Descriptions and stereotypes of sociologists do not typically include a religious dimension. Yet, many of the earliest American sociologists grew up in families with strong religious backgrounds and were men of faith. In fact, some of the heartiest roots of the discipline can be traced to the “Social Gospel” movement. A Protestant Christian intellectual movement that was most prominent in the late 19th and early 20th century, adherents sought to make the Christian churches more responsive to social problems such as poverty, prostitution, child welfare, temperance, and crime. Members of the movement shared a belief in the innate goodness of humankind. They were also post-millennialist: they believed that the Second Coming could not happen until humankind rid itself of social evils. Although the social gospel movement was not a unified movement – followers argued among themselves about specifics – for most the pursuit of social justice and a mission to apply the teachings of Jesus as recorded in the New Testament, especially in his “Sermon on the Mount,” was considered essential. They sought to bring about the Kingdom of God on earth ("Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven," Matthew 6:10). Toward that goal, they applied Christian ethics to social problems, focusing generally on issues of social justice, and most particularly upon inequality and the pathological consequences of the poverty they saw all around them, especially in the newly industrialized cities. Their main concerns included unsanitary living conditions in the slums, dangerous working conditions in the factories, child labor, poor schools, alcoholism, prostitution, and crime, and racial and ethnic tensions. But once established, sociology needed both public and institutional support to grow. The new discipline had to convince colleges and universities that departments of sociology were needed – that it was a “legitimate” area of inquiry comparable to the previously established departments of economics and political science. It had to convince policy makers that the knowledge it produced would be “useful” to policy makers and could help society grapple with the important social issues of the day. As a result, in order to secure public acceptance and legitimacy the discipline became more concerned with packaging itself as a pure science concerned with the strict pursuit of law-like propositions and the development of theory – as seen in the quotes by Ogburn and Park above. Activist and reformist tendencies were re-kindled during the years of the great depression, the civil rights era, the turbulent decade of the sixties, and this past decade as a reinvigorated concern with “public sociology” and “service learning” has taken hold. At other historical moments sociologists, rather than criticizing society, was pressed into its service, working, for example, with the Information and Education Division in the U.S. Army’s Research Branch during World War II. After the war, with the founding of the Bureau of Applied Social Research at Columbia University, an era of “contract work” began, with sociologists now working more closely with government and corporate agencies. At the same time, activist tendencies were somewhat dampened by the advent of McCarthyism – the “red scare” in the 1950s. As it turned out, though not known at the time, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) placed many of the leaders of the discipline under surveillance. It is important to note that the two sides of the debate are not necessarily contradictory or incompatible. Values clearly affect the problems sociologists choose to investigate – and they certainly may reflect their activist or reformist interest, such as the reduction of inequality and poverty and/or the various “isms” – racism, sexism, ageism – that plague society. But once chosen, the problem must be studied in accordance with a strict sociological approach, wedded to the mandates of scientific methodology. To be an activist, then, does not necessarily undermine or compromise the authenticity of one’s work or their scientific standing. |

What is the proper role of a sociologist? |

Before I move on to discussing with more precision what sociology is, the kinds of questions we tend to ask, and the form of the answers we generally give, I’d like you to consider the following questions: What is the proper role of a scientist (and, again, sociologists are scientists)? Do they have any social responsibility to “speak out” and discuss the relevance, importance, and perhaps potential dangers and/or consequences of their research findings in public? Many physicists, you might recall, spoke out about the dangers of the atomic bomb after the United States dropped two on civilian populations during World War II, sparking public debate. Are social scientists better equipped – through their training and adherence to scientific methods – than the common “man on the streets” and politicians who are not typically trained in this area to describe, analyze and interpret the world in which we live? Does the expertise that social scientists possess give them a special obligation to comment on the problems of their times? |

E.A. Ross 1866 - 1951 |

|

Richard Ely 1854 - 1943 |

|

J.L. Laughlin 1850 - 1933 |

|

One last comment before we move on. In today’s day and age, the word “activist” takes on certain connotations. It tends to be associated with either a “liberal” or “radical” political stance. This is somewhat peculiar. Because what should we call a conservative or libertarian who energetically advocates – stands up for or raises his or her voice publicly to either recommend, defend, or criticize – a particular idea or policy? Activists, it seems clear, come in all political shapes and sizes. |

What is Sociology? |

|

C. Wright Mills 1916 - 1962 |

|

Peter Berger 1929 - |

|

John J. Macionis |

|

|

Sociology is the scientific study of social—not biological or psychological—factors that affect the probability or likelihood

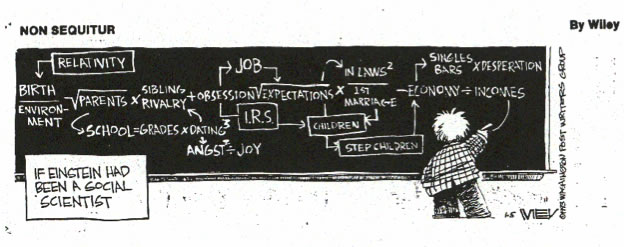

All of these, of course, are inter-related (i.e., social conduct, beliefs, values and attitudes are mutually reinforcing, just as one’s conduct and attitudes affect their performance). Sociology seeks to uncover and then explain the existence of social patterns, and then examine how these patterns contribute to the shaping of future social behaviors and actions that either strengthen, modify, or totally change these patterns of human conduct. Sociologists also investigate how these patterns develop into larger long-lasting and enduring structures – for example, the major institutions in society such as the family, the polity, the economy, education, religion – and what form these larger structures take. As shall be seen, there are many different types of families in the world (and in the United States), many different types of political institutions, many different types of economies and so on. In some societies, wealth and power is concentrated in the hands of the few in others it is widely – though not exactly evenly – dispersed. In a very important and consequential way, social factors affect one’s access to resources and opportunities. As you all know, resources and opportunities are not evenly distributed in society. Just consider the well-known phrase, “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know that is important.” You might be the hardest working, most capable person around, but you still need the opportunity to show folks what you can do. Let me walk you through the key concepts in the way I’m presenting sociology to you. Look at the following diagram. I know it looks difficult, but it is simply showing you visually what’s already been said. What do we mean by social factors? Why is the notion of probability an important part of the approach? What is the difference between action and behavior and between intended and unintended outcomes or consequences? |

Let’s begin with “social factors.” |

Social Factors |

Social factors play a large role in shaping people’s beliefs, values, attitudes—how we think. Equally important, they can facilitate (make easier), hasten (make happen more quickly), constrain (make more difficult), or actually prevent certain types of conduct as well as shape the consequences of that conduct. The term “social factors” defies easy explanation. Most broadly considered, social factors encompass any and all aspects of your immediate environment and of the world at large (yes, things that happen in Iraq or Syria or China can affect you) that involve more than one person or that has been, in the past, the product of people, such as technology and other inventions. These factors are external to the individual – we are enveloped in them just as we are enveloped in the bubble of atmosphere that surrounds the molten rock and oceans of this planet. Social factors are “out there” in the environment, whether one recognizes them or not and, for the most part, they are beyond the control of the people who are affected by them. (Note: As shall be seen, this in no way absolves people from taking personal responsibility for their conduct.) |

Categories of Social Factors: Social Background Characteristics |

(1) Social background characteristics make up one important category of social factors. Your age, sex, race, social class, level of educational attainment, religiousity—and more—clearly affect the likelihood that you will embrace some beliefs, values and attitudes rather than others and will act or behave one way rather than another. Wealthy people, for example, are more apt than poor people to embrace conservative beliefs and attitudes and support the Republican Party. What is it about the experiences of wealthy people – the lives they led – that shape their political beliefs and attitudes one way and the experiences of poor people that shape their political beliefs and attitudes another way? One’s sex also affects the way they think, act, and behave. Just think about the simple act of talking – which is at the core of any social interaction. Watch this scene from Friends. What differences in the way that women and men talk do you notice? |

If any of you have ever spoken with a member of the opposite sex, you probably found the scene familiar – and funny. So, what did you notice? Did you think that the women were more detail oriented – perhaps even more emotional – and the men less emotional and straight to the point? |

Deborah Tannen Georgetown University |

|

|

And let’s be honest here. Guys: how long can you stay on the phone? A minute, maybe two? Ladies? Forever? And, ladies, if there are two chairs in a room, how will you place them when you talk with your girlfriend? Facing each other or side-by-side? Women usually situate them facing each other and, while they talk, make eye contact and provide continuous feedback through facial gestures and verbal responses such as “really,” “you’re kidding,” “s/he did what?” Guys will probably just stand around, not sitting at all, but if they did maneuver the chairs, they wouldn’t be facing each other. Men don’t typically make eye contact with one another – and if they do, it’s only for the briefest amount of time – maybe a second. (Guys: has your female partner ever accused you of “not listening” because you weren’t looking directly at her According to Tannen, the very act of conversing often has different goals. For women, it is rapport. Conversations are used to develop connections, closeness and intimacy. Talk is the “glue” that holds relationships together. Conflict is often perceived as a threat to connection and to be avoided at all costs. Disputes are preferably settled without direct confrontation. This style develops, Tannen argues, quite early in life. Growing up, girls tend to play in small groups or in pairs. They typically have one best friend with whom they share everything: stories, hurts, triumphs, and especially feelings. They take turns when they play and they are cooperative. They are on equal footing. Whereas women seek rapport, men are interested in report. What do I need to know? Tell me and let’s move on. And this style, too, Tannen argues, develops early and is rooted in boys’ different experiences. Boys tend to play in large groups that are hierarchically structured. Someone is on top – it might be because he is the oldest, the biggest, the strongest, the best athlete, the one who is the smartest, the one of with the best wit, using words to push others around and establish his superiority. So, there is a leader who gives orders while others in the group are jockeying around for position. Conversations are negotiations in which boys try to achieve and maintain the upper-hand. And conflict is a means by which one’s position is negotiated. Moreover, Tannen argues that men often use opposition to establish connections. Guy: have you ever had a physical altercation – fight – with someone in the group where you either got the snot beat out of you or kicked someone else’s butt? And by the next day you were friends again – perhaps even better friends than before? It is also important to remember that in any hierarchical group, there isn’t just someone at the top – there is also someone at the bottom. Guys: wasn’t there always someone in the group that was – how can I put this gently – that was a jerk who no one liked? But you kept him around anyway, either for amusement or because you needed him for something – maybe he owned a good football. The point here is that we learned how to deal with jerks. When Tommy acted like a jerk, we didn’t take it personally, we simply all said, “Well, he’s a jerk – and what do you expect from a jerk?” It’s his problem. Now, girls don’t typically have these same experiences. First of all, they don’t typically allow other girls that they don’t like to remain in their group once they are in junior and senior high school. And although girls may be just as likely to use aggression as boys, rather than fists, girls typically express it through manipulation, exclusion, note passing, and gossip. (How many of you have met a girl who would have preferred to be beaten up and friends the next day instead of being the target of gossip that ruined her reputation?) And since the girl no one likes gets kicked out of the group – those who remain rarely get to learn how to deal with the so-called jerk. So, ladies, consider: during the course of telling your male partner about your day, is there usually at least one thing that happened during the day that irritates you? If so, is it typically a situation, or is it a person? Research indicates that it is usually a person that irritates you – often someone at work or in a store. And when you tell your male partner, isn’t this when he usually perks up, taking an interest? Because men want to solve your problem. And we tell you about the jerks we grew up with and how when a jerk acts like a jerk you shouldn’t be surprised or take it personally; that you should just laugh to yourself and not let it bother you. But is this what you want to hear? Or would you prefer your “best friend” of years ago who, making eye contact and the appropriate sympathetic facial expressions, commiserates with you? |

|

|

Tannen also finds that women are less direct when they are in brain storming sessions pitching ideas or in a position to give orders. When pitching ideas women are more likely to downplay their certainty and tend to preface their suggestions with “Maybe we could . . .” or “Perhaps we should consider . . .” while men are more likely to downplay their doubts. Neither Tannen – nor I – are arguing that these differences in genderlects are solely responsible for unequal wages in corporate America, it seems clear that in an institution mostly run by men, constantly saying “I’m sorry” and “thank you” and using an indirect approach in discussions can contribute to being seen in a subordinate position. Now, before any of the women in the class get upset, let me remind you that, again, these differences are general tendencies – nothing is 100%. And no one is saying that one genderlect is in any way better than the other. They are just different. And, in fact, there are also clear differences if people are talking in private or in public. It’s interesting to note that when a couple is asked, “who does most of the talking in the couple,” each says the other one does. The man, of course, is thinking about what goes on inside the home, while the female is thinking about being out in public with other couples, where the men hold forth and tell stories that they never mentioned to their partners when they were asked about their day . . . But to get back on track, we’re focusing upon social background characteristics as one important category of social factors that affects the likelihood that you will embrace some beliefs, values and attitudes rather than others – the example used was political attitudes – and will act or behave one way rather than another – using talk as an example. In addition, social background characteristics will also affect the likelihood that someone will be successful in attaining their goals—regardless of the amount of their personal effort. Would you agree that being a woman affects the probability that she will become President of the United States, reducing it by a considerable margin, or do you actually think that a woman has every bit the same chance as men? |

Categories of Social Factors: The Immediate Presence of Other People |

(2) The immediate presence of other people—some considered very important, others less so—and the groups to which you belong constitutes a second important category of social factors. Here, the mutual expectations people have of one another and the “social rules” or “norms” that govern daily interactions, come into play. How many of you have ever experienced “peer pressure” and done something, in the presence of a group to which you belong, that you know darn well you wouldn’t have done if you were alone? How many of you have modified your actions and behaviors because you knew that certain people, if they found out, would disapprove? |

Categories of Social Factors: Culture |

(3) Broad cultural standards and trends—a peoples’ way of life—and more narrowly defined sub-cultural standards—comprise a third category of social factors. Here, culture refers to all of a peoples' shared beliefs, values, attitudes, norms, customs, traditions, and artifacts (material products such as inventions and technology). These, of course, change over historical time. Imagine how different your life would be if you were born among the Yanomamo Indians (“the fierce people”) or the Asmat of New Guinea (cannibalistic). Would you hold the same beliefs, values and attitudes that you do today? Culture is responsible for deep-seated taken-for-granted assumptions about the world. |

Categories of Social Factors: Social Institutions |

(4) Institutions—such as the family, economy, polity, education, religion, and science—are enduring and complex social structures that are found in nearly all societies. Although overlaps exist, different societies have “socially constructed” (or, invented) these same institutions at different times in different ways. Consider how different your life would be if you grew up in a society where polygamy rather than monogamy was the established family practice, or in a socialist rather than a capitalist economic institution, or in a fascist rather than a democratic political setting. |

Categories of Social Factors: The Structure of Society |

(5) The “structure of society”—for example, the distribution (concentration and dispersion) of wealth and power and the access that is provided to resources—provides another set of social factors that affect the way people think and act. Moreover, they affect to a large extent one’s life-chances in that society. |

Categories of Social Factors: Social Inventions |

6) Last, consider basic social inventions. There was a time when “money” & “credit” did not exist – it was invented for particular reasons and to meet certain needs. Calendars and the seven-day week are also social conventions. In a cosmic sense, each day – each twenty-four hour period that corresponds to the earth rotating on its axis – is precisely the same as any other day. But each “day” has a different socially constructed “feel” to it that imposes a rhythmic beat on the vast array of our social activities, including work, love, and play. There is a hidden rhythm in social living. More people commit suicide on Monday than on any other day. Not having a date on Thursday night is not quite as disconcerting as being dateless on Saturday night. And are you aware that calendars exist in other cultures today that have three ten-day weeks each month, with the last five days of the “year” devoted to festival? |

Probability: “. . . factors affecting the probability or likelihood that . . .” |

No area of inquiry that takes as its subject manner human beings—including sociology, political science, economics, history, psychology, anthropology—can be deterministic. That is, unlike much of physics and chemistry, they cannot tell you with 100% certainty why something has occurred in the past or what will occur in the future. Sociology (and the other social sciences) can, however, indicate what factors will either increase or decrease the probability that something has or will happen. And if, given social circumstances X, Y, and Z, there is a 75% probability that “A” will occur, it is also true that there is a 25% probability that it will not occur. Therefore, for every social pattern you see there will always be counter-examples. Nevertheless, the pattern still exists and will continue to affect the future course of events. That sociology cannot tell you with 100% certainty why something has occurred in the past or what will occur in the future should not surprise you. You can’t tell me with 100% why you have done certain things in your life, and however much you intend to do a particular thing in the future, life often intrudes and changes your plans. So don’t hold us to unrealistic standards. The important thing is to discover patterns – and these are never 100%. It’s not, for instance, that all of the people in one category act a particular way or are experiencing a particular circumstance while none of the people in another category do so. It’s the relative differences that are important. |

If, as you see below, we find that one category of people was eight times more likely to be murdered than another category, we can assume that something is going on that needs to be investigated. |

What is it about being African American that increases the likelihood of being murdered? What is it about being white that reduces the likelihood of being murdered? Once we can demonstrate patterned differences, we now must turn our attention to explaining the pattern. Perhaps the best way to illustrate social patterns is to use visuals. First, watch this brief video on “murmuration” (yes, it’s about birds flocking together). Focus on both individual birds when you can, and the overall pattern of the flock’s flight. |

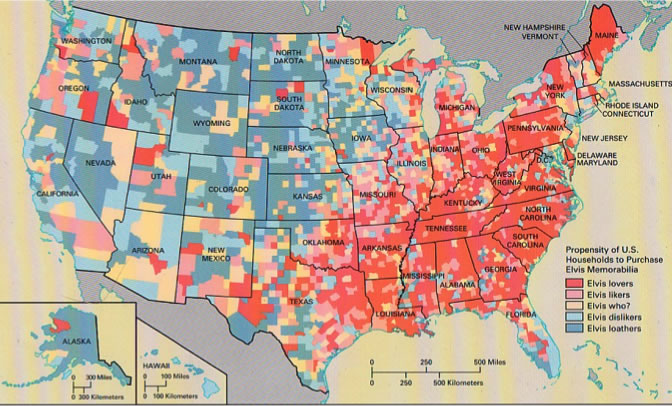

I hope that you noticed that no two birds were doing the exact same thing or flying the exact same path. But I also hope that you did see the pattern and that the flight of the flock had a structure to it – that there was, in fact, a pattern. Now look at the following map: Where are the Elvis Fans? Here you find each state in the U.S. color–coded according to its inhabitants’ tendency or inclination to purchase Elvis memorabilia. Do you notice a pattern, or are the colors randomly distributed? What accounts for these findings? |

|

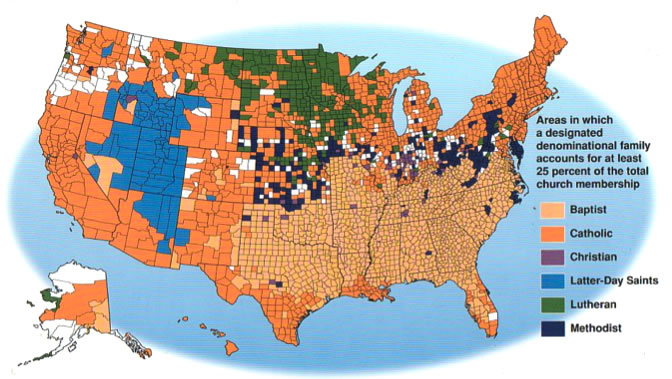

Or how about this map, which shows the distribution of Christian denominations in the U.S. Again, do you see any patterns or are religious groups scattered throughout the U.S. in buckshot fashion, being randomly distributed. Do you see the so-called “Bible Belt?” |

|

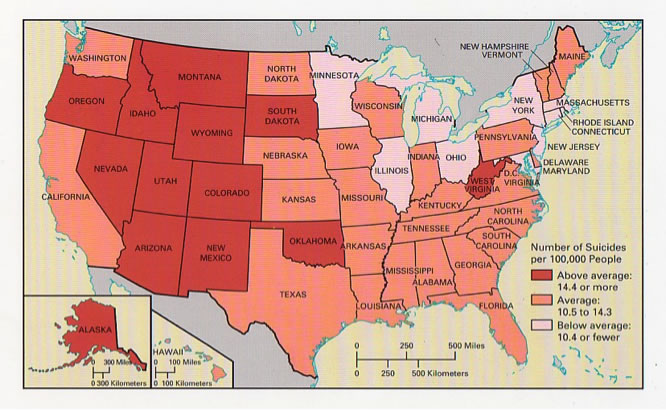

Now look at the distribution of suicide rates in the U.S. Why are people more apt to commit suicides in those states with higher rates? What is about living in Montana, or South Dakota (but not North Dakota) that affects this probability? |

|

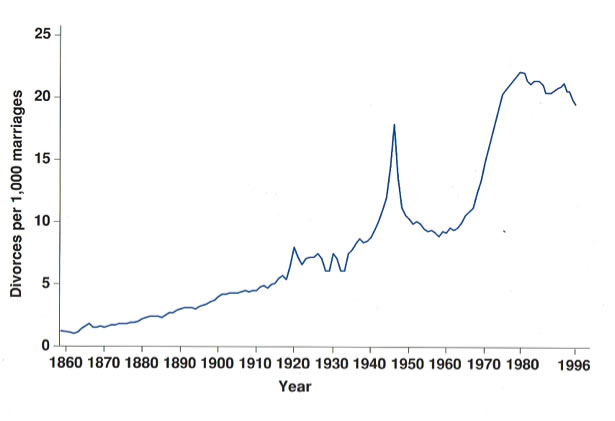

Now look at another way a pattern can be seen: this graph of divorce rates in the U.S. What do you notice? Do you see the blips during World War I and the depression, and the large peaks during World War II and the post-1960s generation? |

|

Action and Behavior: “. . .that people will either act or behave one way rather than another” |

Although Macionis – the author of the textbook – does not make a distinction between “action” and “behavior,” I think that it is important. They are, in fact, two different types of social conduct and the differences are important if you’d like to be able to modify or change one’s conduct. The term “behavior” already had a history when sociologists finally came along. It played an important role in Psychology and, according to “behaviorists such as John B. Watson, behavior referred to unthinking, reflexive responses to stimuli in the immediate environment. In other words, people were not consciously making decisions by weighing alternatives. Compare this to what we will refer to as “action”: here, individuals are consciously making two choices – they are making two decisions. First, they are choosing from among available competing goals or ends – “What shall I do: This or that?” – and second they are choosing from available means to attain those goals – “Should I do it this way or that way?” If you think about this you’ll find that this distinction between behavior and action is of central importance in our criminal justice system when it considers intent or mens rea (which is Latin for a “guilty mind”). Pre-meditated murder – clearly an intended action – will be more harshly punished than “negligent homicide” where no such intent existed. Or consider discrimination. Is it an action or a behavior? Actually, it could be both, depending upon the circumstances. But if a person “acts” in a discriminatory manner, you know that they are making a conscious choice to do so, and by alerting them to the potential penalties – the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission will fine you $250,000 – you may influence the potential discriminator’s decision. But if they are “behaving” in a discriminatory manner – without any thought whatsoever – because it has been so ingrained in their psyche that they don’t even think about it, another solution must be sought. |

Intended and Unintended Outcomes |

As shall be seen when we discuss the various theoretical perspectives in sociology, distinguishing between intended and unintended consequences is of paramount importance. For every action or behavior there are multiple consequences – and the vast majority of them are unintended. This has been noted by scholars who otherwise differ in significant ways. Karl Marx, for example, argued that capitalism had within it the seeds of its own destruction. Non-Marxists (or anti-Marxists) have expressed this in the following folk-maxim: “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” And this is what makes sociology fun. Anyone can discover the intended consequences of one’s actions or behaviors: just ask the person why they did what they did and what their goal was. To discover unintended consequences – that’s where detective work and an active mind come into play. |

Copyright 2013, Larry Stern

All material on this webpage is for Collin College class use only. Any unauthorized duplication or distribution is prohibited.