|

Sociology 1301

|

|

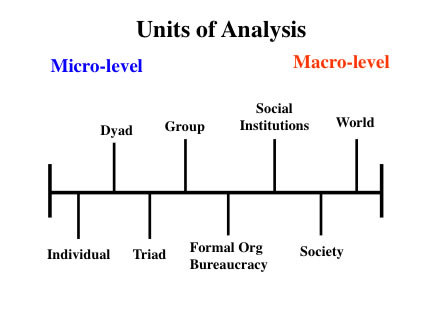

The term “theoretical perspective” refers to broad assumptions about society, individuals, and social behavior that serve as a point of departure for sociological thinking and research. It focuses the analyst’s attention on some aspects of the social world rather than others – think, again, of the analogy of a flashlight in a dark room. It defines some questions as especially relevant and important and others as trivial and uninteresting. In addition, these perspectives may be considered as interpretative schemes: they offer a framework for interpreting the results of specific studies. Here, we will discuss three of the main theoretical perspectives in the discipline of sociology: symbolic interactionist, structural-functionalist, and conflict. No one of these perspectives has successfully dealt with the entire range of sociologically interesting questions. Starting with different sets of assumptions, each perspective focuses on a different range of social phenomena and, as a result, raises different questions. And as shall be seen, each perspective starts with a different idea of how we should conceptualize – think about – human beings. These perspectives should not, however, be thought of as being necessarily at odds with one another. Although sociologists adhering to different perspectives have marked disagreements with one another about the nature of the social world, these perspectives are not necessarily contradictory, nor mutually exclusive in the sense that if one is correct all others must be incorrect. As one noted theorist has commented, “Many ideas in structural analysis and symbolic interactionism . . . are opposed to one another in about the same sense as ham is opposed to eggs: they are perceptively different but mutually enriching.” Together, these three perspectives provide a broader and deeper understanding of the world. As you can see here, there are many different units of analysis that sociologists can choose from, ranging from micro-level (small) phenomena – individuals in their daily face-to-face interactions with one or more people in their local surroundings – to macro-level (large) phenomena such as formal organizations and bureaucracies, or institutions such as the family, or the entire society, all the way up to the world and the ways that entire societies interact. |

|

We will begin at the micro end of the continuum and provide, first, a broad overview of the symbolic interaction perspective. As shall be seen, symbolic interactionists view individuals as active agents that socially construct reality. Next, we will focus on one variation of symbolic interaction known as the dramaturgical perspective. Erving Goffman, the sociologist best known for this approach, views individuals as actors who play various roles in life. We will then discuss a very different way of thinking about individuals – we will think of individuals as occupants of social positions, or statuses, which make up the fundamental building blocks of society. After indicating how these micro-level approaches contribute to our understanding of the social world, we will shift to the macro end of the continuum and discuss structural-functional analysis, which tends to see society as a system with inter-related parts working together to keep society stable, and the conflict approach, which focuses more on conflict, inequality, power differences. |

Symbolic Interaction |

Although the roots of what has come to be called the symbolic interaction perspective can be traced to the German sociologist Max Weber, George Herbert Mead, working at the University of Chicago, is considered to be one of the American founders of this perspective. |

G. H. Mead 1863 - 1931 |

|

It is crucial, symbolic interactionists argue, that peoples’ definition of the situation – what they think about the situation and what they intend to do – must be understood if one wants to make sense out of their behavior. Since action is created by the actor out of what he or she perceives, interprets, and judges, to fully understand it the analyst would have to see the situation as the actor sees it, perceive objects as the actor perceives them, ascertain the meanings they have for the actor, and follow the actor’s line of conduct as the actor organizes it and modifies it during its course. Human beings, then, are conceptualized – thought of – as active agents of their own lives. |

W.I. Thomas 1863 - 1947 |

|

Rather than think of this as an individual phenomenon, consider now a widely shared false definition of a situation – people believing that particular categories of people are inherently less intelligent or capable than others. If you “believe” this, will it affect your decision as to whether funds should be allocated to enrich educational opportunities for those categories of people? |

Symbols |

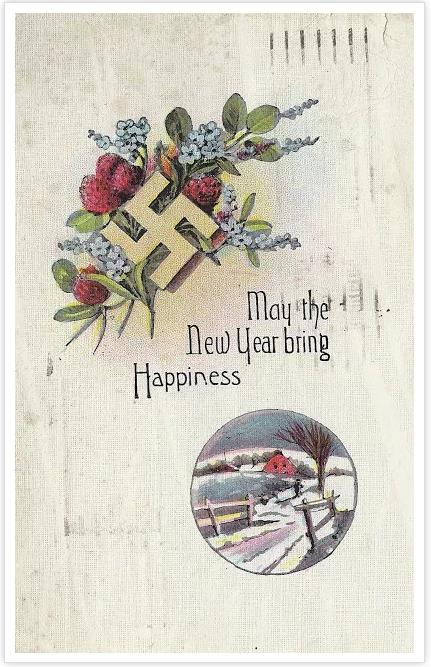

So, what are “symbols” and how are they created, defined, and shared by interacting individuals? And how is “reality” socially constructed from the ground up? A symbol is anything that stands for something other than itself – anything that carries a particular meaning that is recognized and shared by people. It could be a word, a cross, a flashing light, a raised fist, a raised finger, a manner of dressing, a piece of jewelry on a finger, a flag – it could be anything as long as people define it in a certain way. Imagine me standing in front of the room holding two pens (or pencils, or tree branches) side-by-side, and then I throw each on the ground and stomp on them. Will my action upset you? Not likely – although you might find my action peculiar. Now picture me with the same two objects, but a tie them together in such a way that you see it as a “cross” – something that has religious significance for you. Will you now be upset if I threw it on the ground and stomped on it? |

|

|

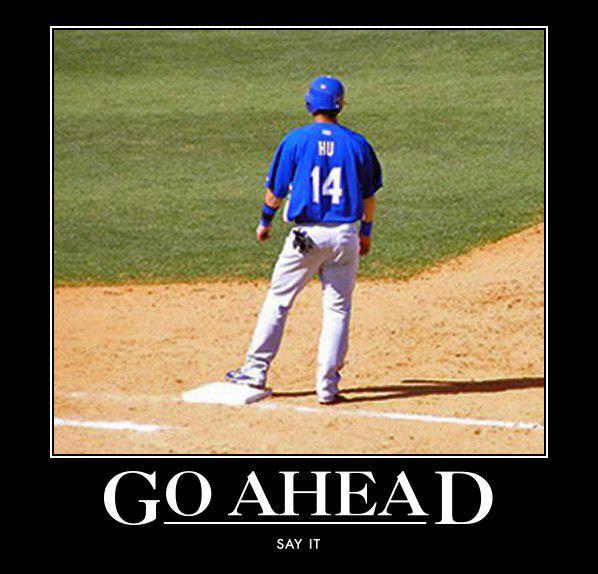

Words, too, are symbols whose meanings change over time. In most instances, the changes can be directly related to particular cultural and/or historical circumstances. Consider the word “straight.” When first introduced, the word had a mathematical and scientific meaning – as in a “straight line,” which is the shortest distance between two points. I won’t go through this word’s entire history, but here are five changes. First, the word migrated into the popular culture of vaudeville and became associated with comedic acts. Back then, you wouldn’t find one comedian doing standup like today – there were comedic teams. One was the “straight man,” the other the “funny man” and they carried on a conversation. The purpose of the straight man was to set up the joke so that his partner got the laughs. [One of the premier “straight” men was Bud Abbot who teamed up with Lou Costello. If you need a brief break, watch Abbot and Costello’s famous “Who’s on First” routine.] |

|

The word “straight” then took on a different connotation during the prohibition era when it referred to a drink “straight up,” or not diluted. Later, being straight with someone meant to be honest and trustworthy. Then, in the 1960s it referred to those who didn’t use drugs. Finally, it now refers to one’s sexual orientation. It is also important to remember that since the meanings of symbols are socially constructed by groups, different groups in the same society may have their own unique set of symbols – there own “argot” or “slang” – that outsiders have difficulty understanding. For example, as my three girls were growing up, they used words like “the bomb,” or “shiznit” (which, to me, didn’t sound like a word meaning “something really cool”). In fact, nearly all sub-cultures have their own language. |

|

|

|

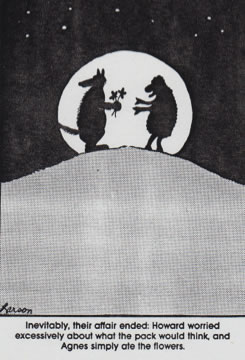

What, in this Far Side cartoon, does flowers signify? An “expression of love,” or “food?” |

|

Since symbols can be defined differently by people in different situations, one must exhibit “interpretative flexibility” when viewing symbols. |

The Dramaturgical Perspective |

|

|

|

|

For example, if individuals were like actors playing roles, how did they know what to say or do? They followed scripts which, as we shall see, are directions or what sociologists call norms or guidelines for behavior that reflect sets of socially defined expectations – how you are supposed to behave in particular circumstances. Actors also use props and wear costumes that convey meanings to others in the interaction and when preparing for one’s role individuals often rehearse their performance (although, as the next Far Side cartoon indicates, it doesn’t always go smoothly!) |

|

Goffman was able to draw additional insights into social interaction by differentiating between front stage – where the actor’s performance is totally visible to the audience – and back stage – where, though still in one’s role, the audience is absent. Consider that when you are in your role as student in class, your actions are visible to your Professors and fellow students. While working at home alone in that same role – doing your class assignments – your behavior is not visible. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Goffman also distinguished between what he termed expressions-given and expressions-given-off. The former, “expressions-given,” are under the control of the actor – he or she is attempting to convey information either verbally or non-verbally through body language and facial gestures. The opposite is true for “expressions-given-off.” Here, although the actor is trying to certain convey information, he or she is perceived, for example, to be insincere, having an “attitude” or as coming off smug in their interactions, though not realizing this to be the case – it is not under their control. This, of course, compromises one’s efforts at impression management, making it problematic. Another thing that affects one’s ability to manage the impression others have is physical disability or some other stigma. Goffman’s next book, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, deals specifically with this issue. The symbolic interactionist perspective is a powerful tool that deepens our understanding of how people create, define, and then use symbols to guide their interactions in specific situations. It sees the macro-level society that we inhabit as socially constructed – as built up from and the sum total of the countless micro-level interactions of individuals. This perspective will be applied throughout the remainder of the course to the various topics and issues that will be covered. But like all perspectives, it is incomplete – not because it is deficient, but because it is intended to address some aspects of social living and not others. Another way that sociologists conceptualize – think about – human beings is as an occupant of social positions, or statuses, and it is to this that I now turn. |

Social Statuses, Status-Sets, Roles and Role-Sets |

Sociologists using this perspective start with the assumption that society is made up of social positions. These social positions – what sociologists call social statuses – are the “building blocks of society." Although some new positions are added in particular circumstances, these positions, for the most part, have been socially created and defined by earlier generations and they tend to exist beyond the lifetime of any one individual. For example, the social position of “father” has been around for sometime and will likely exist well after you and I leave this earth. |

Social Statuses – Positions in Society |

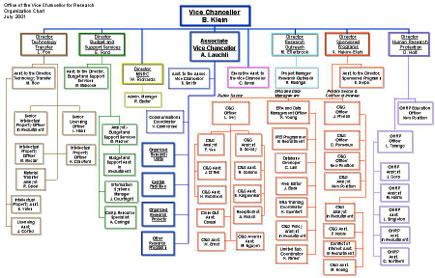

Perhaps the best way to visualize this – as a first approximation – is to look at this organizational chart. |

|

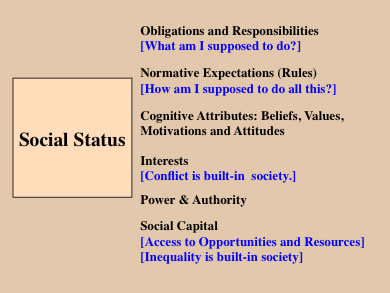

Here, each “box” represents a social position in the organization and, as you can see, the positions are not randomly distributed, they are organized in a particular (color-coded) way. So if, for example, someone occupying one of the lavender boxes has a complaint, they would go to the person in the purple box above them – not to someone in a brown, green, yellow, or blue box. There is a chain of command. Moreover, although individuals who occupy these positions might move fluidly from one to another – due to promotions – the overall structure of the organization – the way it hangs together – remains the same. It is also the case that each box – each social position – has a job description attached to it and whoever occupies that position must follow it to a certain extent or suffer the consequences. Think, now, of society like this. It is made up of countless social positions – social statuses – each having a sort of job description – and more – attached to them. And each of the color-coded columns represents an institution in society – the polity, economy, family, religion, education – and each box in the column is a specific position or status in that institution – President or Congressman, factory owner or worker, father or uncle, Deacon or parishioner, teacher or student. As the next chart indicates, there are five different attributes of a social status. Attached or built-in to each status are (1) responsibilities and obligations, (2) norms (or, rules), (3) interests, (4) power and authority, and (5) social capital (opportunities and resources). |

|

Obligations and Responsibilities |

Associated with each social status is a set of obligations and responsibilities that, at any one time, are socially defined. They are “expectations” of how the individual who occupies the status should act. These indicate what status-occupants are supposed to do. Fathers, for example, are expected to provide for their families. Professors are supposed to arrive on time, impart relevant information, evaluate their students performance, return written work in a timely manner, and so on. Students are expected to come to class, keep up with their assignments, complete exams, and so on. Since these expectations are “socially defined,” they can of course change over time. A father in the 1950s was not expected to change diapers or to be as involved in childcare as are fathers today. A professor in the 1950s did not likely show up for class wearing jeans, a three-button tee-shirt, and Vibram five-finger toe-shoes. And this is not to say that each and every status occupant lives up to the responsibilities and obligations to the same extent – not all fathers, or professors, or students are exactly alike. There will be, of course, “family resemblances.” Although the actions of all those occupying the same status varies somewhat, they are variations of the same theme. The key point is that individuals who occupy a given status must take these responsibilities and obligations into account. They know that not living up to the responsibilities and obligations associated with their statuses can have adverse consequences. |

Social Norms |

There are also sets of norms – guidelines or rules – that are associated with specific social statuses and which indicate how you should act and/or behave in specific situations. There are (at least) ten characteristics or attributes of norms.

|

Cognitive Attributes: Beliefs, Values, Motivations and Attitudes |

Specific sets of beliefs, values, attitudes and motivations are also associated with social statuses . . . Each of us not only knows, for the most part, what is expected of us when we occupy a particular status, we also have a sense – based on our past experiences – of what is expected of others with whom we interact, even if we have never occupied the same status that they occupy. In other words, each of us possess a vast storehouse of “social knowledge” and, to varying degrees, knows not only what is expected of us, we also know what to expect of others. For example, none of you have ever been a Professor, but you all have certain expectations of what I am supposed to do – my responsibilities and obligations – and how I am supposed to do those things – the norms I take into account. These shared reciprocal expectations are mutually reinforcing and account, in no small part, for the stability that we see in society. |

Interests |

At the same time, however, because different specific sets of legitimate interests are also associated with particular social statuses, conflict is inevitable – it is built-in the fabric of society; it is structurally induced. As a result, people who occupy different social positions – by virtue of occupying different positions – will have different sets of legitimate interests. The main interest of a corporate Chief Executive Officer (CEO) is to increase profits for the company and its shareholders – this is why he or she was hired. The the main interest of an employee in that corporation is to receive adequate compensation – a decent wage and benefits package – for living up to the responsibilities and obligations of their position. The vast majority of conflict, then, that occurs in society is the result of people – status-occupants – pursuing the interests that are associated with their statuses. In many cases, individuals who occupy the same status, realizing that their interests could be better served by joining together, form what political scientists refer to as interest groups. Examples are the American Medical Association (AMA), an interest group made up of doctor’s pursuing their interests, the American Association of Retired People (AARP), and the National Rifle Association (NRA). As shall be seen, the idea that individuals occupying different positions have different interests which inevitably leads to conflict is at the core of Karl Marx’ analysis of society. |

Power and Authority |

If conflict is built-in to the very fabric of society, how is it managed? How are conflicts - whether legitimate or not - resolved? Here, both power and authority come into play and these, too are associated with statuses. Let’s first distinguish between these two concepts. Power is the capacity to impose one’s will over others, even against the resistance of those others – it implies coercion. Authority is the capacity to have others comply with your wishes – even if they would prefer not to – because they recognize the legitimacy of the request. Most folks tend to think of power or authority as an “ability” or “attribute” of individuals: their personal physical or mental strength or their force of character that allows them to enforce their will over others. But they are not individual abilities or attributes, they are capacities located in the positions (statuses) people occupy. The President, for example is the most powerful man in the U.S., but that power is not his to keep. The power is located in the “office” – position/status – of the President and once the President leaves office, the power remains there for the next incumbent. Nor is the extent to which power is exercised by status-occupants always the same. As President, Dwight Eisenhower was less apt to exercise the full power of the office; Richard M. Nixon went beyond its boundaries (the House Judiciary Committee’s second article of impeachment was for his abuse of power); George W. Bush sought to enlarge the power of the Presidency. It is important to note that both power and authority are not equally distributed in all social statuses: employers typically have more than employees, professors more than students, the Dean more than professors, men more than women, the wealthy more than the poor, light-skinned people more than those with darker complexions. As a result of these differences in power and authority, we expect, and unfortunately find, different outcomes in society, such as unequal pay for men and women, stark disparities in sentencing of members of different races found guilty of the same crime. |

Social Capital |

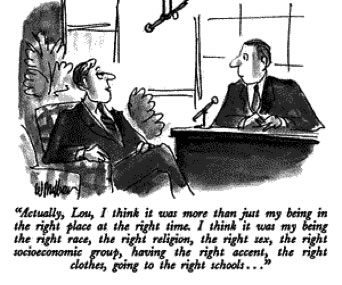

The last attribute of a social status we will consider is social capital.This refers to the opportunities and resources that are available to status-occupants and this, too, in unevenly distributed among statuses in society. Much of this is captured in two well-known phrases, “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know” and “being in the right place at the right time.” The gentleman in the cartoon below actually misses the point. He was in the right place at the right time because of the statuses he listed that he occupies! |

|

Networking, we all know, is rather important when searching for jobs. “Putting the word out” among your friends and associates or using such web sites as “Linked In” is one example. But also consider how many jobs are filled through nepotism: where favoritism is granted to family members or close friends regardless of merit. Although access to opportunities and resources doesn’t ensure one’s success in life – some people waste opportunities and resources or simply do not have the ability or whatever it takes to convert these into successful outcomes – occupying statuses with enlarged access certainly increases the probability that one will “get ahead” in life. As shall be seen later in the semester, the differential access to opportunities and resources that comes with occupying certain statuses, when acted upon, is a contributing factor to the inequality that we find in society. As mentioned earlier, social statuses are the building blocks of society. And thinking of individuals as status-occupants helps us understand why people act and behave as they do. Thinking this way also helps us understand the existence of three important aspects of society: stability, conflict, and inequality. Our knowledge of what is expected of us when we occupy certain statuses – and what we should expect of others in their statuses – contributes to stability in society. Our reciprocal and mutually held expectations grease the wheels of our interactions. The different interests that occupants of different statuses legitimately hold indicates points where conflicts are to be expected and shows that they are built-in the fabric of society. And the differing amounts of access to opportunities and resources that come with status occupancy indicates how inequality can emerge and be maintained. But to say that occupants of statuses take these five elements into account is not to say that each and every status occupant lives up to the responsibilities and obligations to the same extent, follows the norms in exactly the same way, pursues their interests to the same extent, exercises their power in the same way, or successfully utilizes the social capital at their disposal. Great variability exists. However, there certainly is a “family resemblance” of all occupants of the same status. Patterns of action and behavior are the direct result. One important reason why there exists only a “family resemblance” is that we do not occupy only one status – we occupy many. So let’s explore what happens when we think in terms of status-sets – the entire array of statuses that an individual occupies – and the insights we can gain. |

Status-Sets |

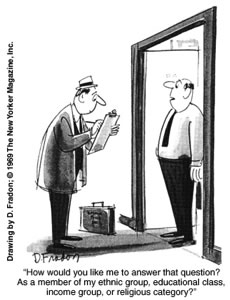

Conceptualizing – thinking about – individuals as occupying multiple statuses – as having their own unique status-set – forces us to consider a number of things and generates interesting questions. For example, you have probably heard the phrase, “All x’s are alike” – just fill in the “x”: all men are alike, all women are alike, all lawyers are alike, all doctors are alike, all rich people are alike, all poor people are alike, and so on. Of course, this is not true. But, why? The main reason – and it becomes obvious once you take seriously the idea that all individuals have their own status-set – is that “x’s” don’t exist! Given the dozens of statuses that make up our status-set, no one is an “x,” each of us is an entire alphabet. You cannot think of an individual as only one thing. Men are not just men. Some men are young; other men are old. Some men are white; other men are people of color. Some men are northerners; other men are southerners. Some men are rich; other men are poor. No two men will have the exact same configuration of combination of statuses in their status set. No two women will have the exact same configuration of combination of statuses in their status set. No two lawyers will have the exact same configuration of combination of statuses in their status set. In fact, no two people will have the exact same configuration of combination of statuses in their status set – we are all unique. Although this might seem obvious to you now, I can assure you that people still slip up on this. Have you ever heard of the Log Cabin Republicans? Founded by gay and lesbian Republicans, this organization works within the Republican Party to advocate equal rights for gays and lesbians in the United States. In fact, a substantial number of members of the gay and lesbian community supported George W. Bush during the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections – and many people couldn’t understand why, given Bush’s stance on marriage and other issues important to the LGBT community. But remember: gay and lesbian individuals are not only gay or lesbian. Each occupies dozens of other statuses, some of which lead them to support conservative Republican positions on matters they deem important – matters that they believe take precedence over their individual concerns. Some are corporate executives who support conservative economic policies. Some are military and support the Republican Party’s foreign policy. As this example also illustrates, since everyone occupies multiple statuses – and each status has its own set of beliefs, values, attitudes, and interests attached to them – we are all often faced with inconsistencies. This is illustrated in the following cartoon, where an individual, responding to a public opinion pollster, makes the point that his answer will differ according to the interests attached to one status rather than another. We are all faced with this – no one’s status set is ever made up of statuses that mesh together with perfect consistency. The interesting question is how are the inevitable inconsistencies that arise managed? |

|

Master Status & Status Activation |

In many instances one’s master status comes into play. A master status refers to that status within an individual’s status-set that has special importance for social identity, often shaping a person’s entire life. Others tend to “see” or define that person as an “X,” rather than any of the other dozens of statuses the person occupies. Brad Pitt, for example, is seen as an actor more so than as a father or son or any of the positions he occupies in charitable organizations. This can be looked at from the standpoint of the actor and from the standpoint of the other person involved in the interaction – and they don’t always agree. A male interested in one of his female classmates wants to activate the status of “boyfriend,” but the woman sees him only as a “friend.” How is this “socially negotiated” by partners in interactions? How are discrepant activations resolved? As shall be seen later this semester, the problem of status activation is central to the workings of prejudice and discrimination in society. Here, someone activates another person’s racial or sexual or age status even though each is irrelevant to the situation. For example, when applying for a job people typically highlight their past accomplishments – activating their occupational status. If the employer refuses to hire people of a particular race they are, in effect, activating the applicant’s racial status – which has nothing whatsoever to do with their abilities to fulfill the responsibilities and obligations of the job. |

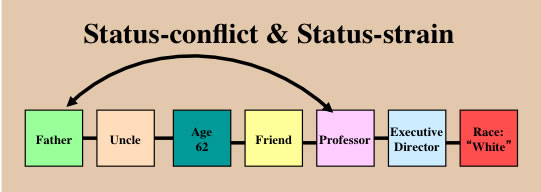

Status-Conflict & Status-Strain |

We all experience conflicts and strains because competing demands are made upon us by virtue of the different statuses we occupy. We are constantly being pulled in different directions. Reading this, you are fulfilling the obligations that are attached to your status of student. But how many of you have other obligations that you also must meet by virtue of occupying other statuses – such as mom, dad, wife, husband, friend, salesperson, hostess – that you have put aside while you finish your school work? Status-conflict and status-strain are the result of incompatible demands that arise from occupying two or more different statuses. |

|

Status-conflict refers to a situation where attending to the demands and obligations of one status precludes fulfilling the demands and obligations of another status. For example, my status “Professor” obligates me to be at school to teach a night class that meets from 7:00 to 9:45. At the same time, because I am also a “father,” I am expected to attend my child’s teacher-parent meeting that is scheduled at the same time. I cannot be in both places at the same time. By fulfilling the demands and obligations of one of these statuses I cannot do the other – as a result I am experiencing “status-conflict.” Status Strain refers to a situation where you could, theoretically, fulfill all of the demands made upon you by different statuses, but you must prioritize your actions and perhaps “cut some corners” in fulfilling your obligations. For example my status “Professor” obligates me to attend a faculty reception that is scheduled from 7:00PM to 9:00PM. But as a father I am expected to attend my daughter’s High School soccer game that is scheduled for the same time. I resolve these competing demands by attending only the first hour of the faculty reception – I leave early – and I arrive late but in time to see the second half of the soccer game. I fulfill the obligations of both, but at less than peak efficiency, and I am experiencing status-strain. |

Role-Sets |

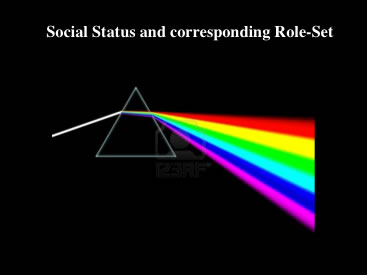

| We can “unpack” a status and break it down into its corresponding roles, which is called a “role-set.” The role-set is the equivalent of a status – it is not attached to a status (as Macionis defines it) – it is simply another way of thinking about a status. As an analogy, think of a beam of light passing through a glass prism and being broken up into different colors of the spectrum. The different colors are not attached to the white light, they are separate and different parts of it. |

|

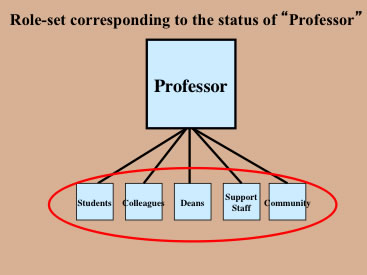

All of the responsibilities and obligations, norms, attitudes, interests, power and social capital that are associated with a social status can now be more precisely located. Consider, for example, the role-set that corresponds to the status of Professor pictured below. I have different responsibilities to my students than I do to either my colleagues, the Dean, the support staff or the community at large. Different norms apply when I interact with each of these role-partners. And while I might have more power and authority as a Professor than my students, my Dean certainly has more power than I do. |

|

And just as conflicts and strains are associated with the occupation of multiple statuses, there are strains and conflicts associated with the multiple roles found in one’s role-set. |

Role-Conflict & Role-Strain |

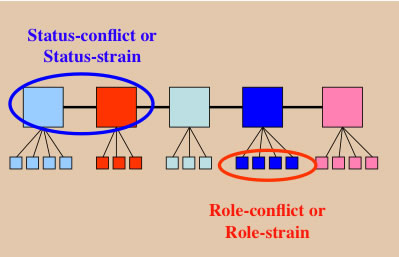

Role-conflict and role-strain are the result of incompatible demands that arise from two or more roles that are found in the role-set that corresponds to one status. Role-conflict refers to a situation where fulfilling the obligations of one role makes it such that you cannot fulfill the obligations of another role associated with the same status. For example, both students and colleagues are members of the role-set that corresponds to “Professor.” On occasion, I am obligated to attend committee meetings with my colleagues at the same time that I schedule office hours to meet with students. Role-strain refers to a situation where you can fulfill the obligations of two roles competing for your attention, but as in the case of status-strain, you don’t give each the full attention that they demand. As the following chart shows, the main difference between status-conflict/status-strain and role-conflict/role-strain is the source of the incompatible demands made upon the individual. If the competing demands are associated with two or more statuses, you are experiencing either status-conflict or status-strain. If the competing demands can be located in the role-set associated with only one status, you are experiencing either role-conflict or role-strain. |

|

Copyright 2013, Larry Stern

All material on this webpage is for Collin College class use only. Any unauthorized duplication or distribution is prohibited.