|

Sociology 1301

|

|

Macro-Level Analysis: The Structural-Functional Perspective |

If individuals are complicated and difficult to fully understand, imagine how difficult it is to think about an entire society with three hundred million people. How have sociologists conceptualized – thought about – society? Here, I shall discuss two perspectives: structural-functional theory and conflict theory. Each of these perspectives can be traced back to the founding of the discipline of sociology. Although, as Macionis (the author of your textbook) – points out, the roots of the structural functionalist perspective in sociology may be found in the works of three of the discipline’s founders – Comte, Spencer, and Durkheim – today this perspective is ordinarily associated with the work of Talcott Parsons, who was located at Harvard University and Robert K. Merton, a student of Parsons at Harvard who then spent the bulk of his career at Columbia University. Since each of these theorists view things somewhat differently, I shall briefly outline the approach of each. |

Talcott Parsons |

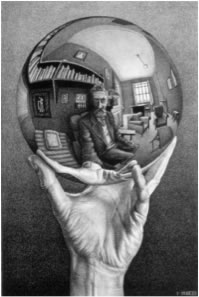

Talcott Parsons 1902 - 1979 |

|

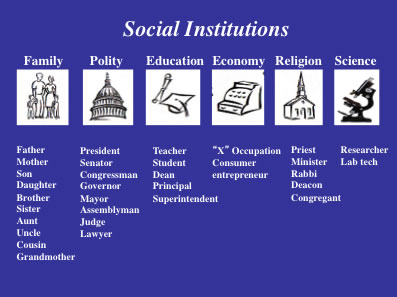

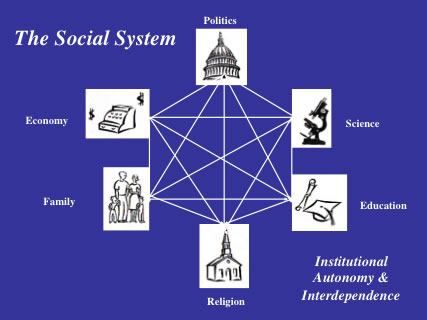

Consider, for example, the idea of a system applied to physiology. The body is made up of specialized organs – such as the brain, heart, lung, kidneys, liver, and pancreas – with each serving specific functions that keep the individual healthy. The heart pumps blood throughout the body, usually beating from 60 to 100 times each minute; kidneys filter roughly 200 quarts of blood each day, removing wastes and extra water that pass out of the body as urine; lungs expand and contract up to 20 times a minute to supply oxygen to capillaries so they can oxygenate blood, as well as remove carbon dioxide that has been created throughout the body; more than 500 vital functions have been identified with the liver related to digestion, metabolism, immunity, and the storage of nutrients within the body; the pancreas help break down carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and acids and secretes such hormones as insulin and glucagon (which regulate the level of sugar in the blood); the brain . . . well, the brain runs the whole show! Remember, too, that these organs (parts of the system) are interconnected. If I go jogging, my heart rates increases from 70 beats per minute to around 110 and this change then affects the functioning of all of the other organs. My lungs work a bit harder, my brain releases adrenaline (endorphins if I run a marathon), and so on. Once I complete my five mile run, I then walk in order to “cool down” – which simply means that my body will soon return to its normal resting state – what physiologists call homeostasis. It is as if the body has an internal thermostat that regulates its functions, keeping the body in a stable state of equilibrium. If, at any time, either organ fails to function properly, the body’s state of health is compromised, in a worst-case scenario, leading to death. It is this imagery of a system that Talcott Parsons used: he visualized society as a social system. Like all systems, society was made up of many different parts, or structures, each with a particular set of functions that contributed to the smooth operation of the entire society. For Parsons, society’s institutions – relatively stable and enduring patterns of behavior such as family, polity, economy, education, and religion – are the basic parts or structures of the system. The basic building blocks of each institution were, as was mentioned earlier social statuses and roles and these, too, have functions. Take, for example, the institution of the family. A structural functionalist would argue that there are specialized statuses and roles within most families, such as mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, and children, each with distinctive obligations, responsibilities, and norms (expectations and guidelines) that govern their behavior. When these are adhered to, the family unit remains stable and functions smoothly and this, in turn, maintains the stability and smooth functioning of the society as a whole. |

It is this imagery of a system that Talcott Parsons used: he visualized society as a social system. Like all systems, society was made up of many different parts, or structures, each with a particular set of functions that contributed to the smooth operation of the entire society. For Parsons, society’s institutions – relatively stable and enduring patterns of behavior such as family, polity, economy, education, and religion – are the basic parts or structures of the system. The basic building blocks of each institution were, as was mentioned earlier social statuses and roles and these, too, have functions. Take, for example, the institution of the family. A structural functionalist would argue that there are specialized statuses and roles within most families, such as mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, and children, each with distinctive obligations, responsibilities, and norms (expectations and guidelines) that govern their behavior. When these are adhered to, the family unit remains stable and functions smoothly and this, in turn, maintains the stability and smooth functioning of the society as a whole. |

|

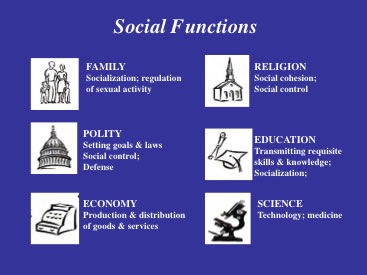

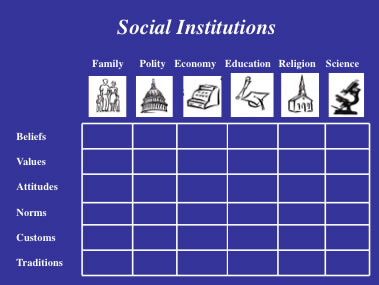

One of Parsons’ key assumptions is that the overall stability of society is maintained because most of the people – clearly not all of them – most of the time – certainly not all of the time – believe in the legitimacy of and share the same beliefs, values, attitudes, norms, customs, and traditions. They share, in other words, a common culture (a concept we will turn to in the next unit) that binds both people and institutions into a coherent whole. Processes of socialization – whereby individuals learn about their culture and how they ought to think, behave and act – and mechanisms of social control – such as peer pressure and laws – contribute to creating and maintaining the stability of society. Sociologists working in this perspective began to specialize in one or more of the institutional spheres and set out first, to determine the different types of institutional patterns that exist. Families, for example, may be nuclear, extended, blended, single-parent, same-sex or some other structural arrangement; the polity may be a participatory democracy, totalitarian, or some other structural arrangement; the economy may be based on a simple barter system, some form of capitalism, socialist, or some other structural arrangement; and so on. Next, sociologists sought to discover how these institutions functioned and contributed to the stability of the entire society. Put briefly, the family, it has been argued, functions or contributes to the stability of society by regulating the reproductive process, ensuring that dependent children will be cared for by their parents, and by transmitting cultural beliefs, values, and attitudes to the young through a process called socialization. The political institution is responsible for, among other things, the defense of our territorial borders, the setting, through elected officials, of our nation’s goals and priorities, and social control. The economy functions to produce and distribute needed goods, such as food, clothing, and shelter, and services to members of society. Our educational institutions contribute to the overall stability of society by teaching members of society the needed skills and knowledge necessary for them to be productive members of society. Our religious institutions both promotes social cohesion among the members of society and serves as a means of social control by instilling morals and values that make it less likely that individuals will take advantage or harm one another. Science produces improved technology to fight disease (and wars), as well as pushing the frontiers of basic knowledge further and further. |

|

Should any of these institutions fail to fulfill their functions or “break down,” society would have serious social problems. Once sociologists were able to identify the various types and forms of institutions in society and how each one functioned to keep society stable, they turned their attention to how these institutions were interrelated – and things, of course, became more complicated – and more interesting! |

|

It isn’t just that, as with all systems, whatever happened in one part – institution – has consequences that affect all of the others. It is fairly obvious that an economic recession, initially located and analyzed with reference to the economic institution, would certainly have political repercussions as well as put severe pressure and strain on families. Or that a war, initially located and analyzed with reference to the political institution, would have on impact on the economy and the family. We also find that by thinking about a society as a social system with separate and independent parts we can’t help but realize that each institution has somewhat different – in some instances even contradictory – beliefs, values, attitudes, norms, customs, and traditions associated with them. As a result we can locate potential areas of cleavage and conflict that is “built-in” society – it couldn’t be any other way. Look at the boxes in following chart and try to fill them in. Are “family values,” “economic values” and “political values” similar or different? Are “religious beliefs” compatible with “scientific beliefs?” |

|

But let’s now return to “thinking about” the intersection and interaction of these institutions. Once the potential incompatibilities and internal contradictions that are built-in society are recognized – once it is understood that these are inevitable – we can better understand the root causes of many of the controversies that occupy society today and how they play out. |

Billy Graham 1918 - |

|

In some controversies, such as whether the theory of “intelligent design” should be taught side-by-side with the theory of evolution in biology courses, we find each institutional setting represented and, as expected, representatives located in each have a different point of view! |

|

|

Although, it is in the interests of certain religious groups that this theory be included in science courses – and that the widely accepted theory of evolution has no basis in fact, scientists argue they are the only ones qualified to decide whether or not something qualifies as “science,” and that the overwhelming consensus is that the theory of intelligent design most assuredly does not qualify. Therefore, it should not, most scientists maintain, be placed in any science curriculum. Even so, some local school boards have done so. In the end, whether or not the theory intelligent design stays in public schools, colleges, and universities will depend upon legal decisions that play out in the political sector of society. In the most recent case, Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District (2007), the courts agreed with scientists that intelligent design was a religious argument and not a scientific theory and that its real purpose, which was to promote religion in the public school classroom, was a violation of the “Establishment Clause” of the United States constitution which forbids the enactment of any law “respecting an establishment of religion.” |

Robert K. Merton |

Robert K. Merton 1910 - 1992 |

|

Multiple Consequences |

First, Merton believed that Parsons and other functionalists had generally, and unnecessarily, restricted their analysis to society as a whole. By restricting their analysis to how the consequences of institutional patterns contributed to the functioning of the society, analysts ignored equally important consequences for other social units such as individuals, groups, social categories (such as race and class), organizations, institutions, and cultural items. Merton argued that all social actions have multiple consequences and the same action, at one and the same time, may have different, even contradictory consequences for different social units of analysis. This not only focuses our attention on the internal contradictions of the social world, it also considerably broadens our analysis and therefore deepens our understanding of certain social phenomena. |

Functions and Dysfunctions |

Merton’s second concern was that Parsons’ brand of functional analysis placed too much emphasis on functions and the stability of the system. Merton agreed that the concept of functions, defined as consequences that contribute to the maintenance and stability of a given system, was important. But, just as some patterns of behavior contribute to the maintenance of the system, they can also lead to consequences that are disruptive. Merton called these dysfunctions. For Merton, the concept dysfunction forces us to think about the strains, stresses, tensions, and contradictions that are built in the structure of society. Whatever order and stability one sees in society, Merton argues, is always precarious and fragile. This underscores a fundamental difference that Merton had with Parsons, who believed that society has an underlying tendency to be stable and somewhat more resistant to change. People often mistakenly believe that the term “function,” since it describes a state of stability, is necessarily good, positive and desirable while the term dysfunction, since it means disruption, implies that it must be bad, negative or undesirable. It is important that you avoid this mistake. While your evaluative assessments are of course important, there is nothing inherently positive or negative, good or bad, desirable or undesirable about either stability or disruption. You might just as easily believe that something that contributes to stability is undesirable because it leads to rigidity and stagnation (there really can be too much of a good thing). And you might believe that war, though clearly disruptive to society, is nevertheless the proper course of action. The point, again, is that there is no inherent evaluation in either of these concepts. They are simply descriptions of a particular set of consequences that flow from social actions. And remember, since all actions have multiple consequences, and these consequences will vary depending upon what our unit of analysis is – a specific individual, a particular group, a category of people, an organization, an entire society – the same action, at one and the same time, might be functional for some, while dysfunctional for others. |

Manifest & Latent Consequences |

A third concern that Merton held was analysts often confused the subjective and conscious motivations of actors with the objective consequences of those actions. The reasons advanced by people for their behavior, Merton stresses, are not necessarily identical with the observed consequences of their behavior. To highlight this important difference, Merton introduced the distinction between manifest and latent consequences. Manifest functions and dysfunctions refer to those consequences that are intended and recognized by participants (individual actors, groups, organizations, society). Latent functions and dysfunctions refer to those consequences that are neither intended nor recognized by actors. Although the idea of unintended consequences appears in popular culture – the To provide another example: I assume that the intended consequences of attending Collin College is to get an education and/or training that will be of some benefit to you – this is a manifest function. But can you think of any latent functions – like making new friendships – or latent dysfunctions – like having to cut your work hours and salary – that also occur because you attend classes at Collin? |

Conducting a Functional Analysis – Poverty |

How, then, should a functional analyst proceed? According to Merton’s perspective, the analyst should examine each social action by asking, “What are the manifest and latent functions and dysfunctions of the action for a range of social units of analysis, including individuals, groups, social categories, organizations, institutions, and society as a whole. Consider the following example, which is illustrative rather than exhaustive, of a functional analysis of poverty in the United States. When asked to list the consequences of poverty, most people tend to focus on its disruptive aspects – its dysfunctions. Poverty is clearly disruptive for those impoverished: they are typically malnourished, live in substandard housing in unsafe neighborhoods, lack access to health care and good schools and, of course, children living in poverty are at greater risk of behavioral and emotional problems. And, of course, many argue that poverty is quite disruptive for society at large, since it is associated with a range of social problems. At the same time, critics argue that huge expenditures to fund and administer so-called “entitlement programs” (i.e., welfare, food stamps) contribute to our national debt, which they argue is spiraling out of control. However valid these arguments might be, application of the functionalist perspective forces our attention on the functions of poverty, too. For example, the existence of poverty ensures that society’s “dirty work” will be done. Impoverished individuals provide a low-wage labor pool that is willing or, due to circumstances, is unable to be unwilling, to do the physically dirty or dangerous, temporary, dead-end and underpaid, undignified and menial jobs that society needs to be filled. That is to say, poverty is functional for certain businesses and groups that profit from those businesses. Poverty, in fact, creates certain types of jobs that would otherwise not be needed – just think of the entire bureaucracy devoted to unemployment benefits. Since the poor are more likely to volunteer to be human guinea pigs for medical research, poverty has also helped pharmaceutical companies conduct needed research of new drugs to combat various diseases. By buying discounted goods such as irregular clothing, day-old bread, and other perishable items whose expiration date is at hand, the poor thus provide at least some return on the costs of production of items that would otherwise be taken off the shelves and thrown away. All of these functions are latent – that is to say, they are unintended. We do not create poverty with the intention of providing jobs or improving our medical research. It is also important to note, as Merton makes clear that to say that a particular social pattern is in some ways functional is not to say that that social pattern is the only way that stability may be achieved; there could be a number of different social structures that might fulfill the same function. To place emphasis on this basic point, Merton introduces the term functional alternatives. To acknowledge that one of the functions of poverty is that society gets its dirty work done is not to justify the existence of poverty. There are certainly other ways to meet those needs. But, as Merton stresses, “any attempt to eliminate an existing social structure without providing adequate alternative structures for fulfilling the functions previously fulfilled by the abolished organization is doomed to failure.” The structural functionalist perspective championed by both Parsons and Merton, by all accounts, dominated the field of sociology from the 1940s through the early 1970s. Although no longer dominant, it is still a powerful guide to research in the field. |

Macro-Level Analysis: The Conflict Perspective |

|

|

As did others, Marx also visualized society as a social system made up of inter-related parts. But for Marx, the economy provides the foundation on which all other social and political arrangements are built. He believed that family, law, philosophy, religion, science, and even art all develop and adapt to the economic structure; in short, each of these other parts of society are determined by economic relationships. Because Marx saw all human relations stemming ultimately from their positions in the economy, he suggested that the major goal of a social scientist is to understand economic relationships: Who owns what, and how does this pattern of ownership affect human relationships? Marx did not see a smoothly functioning society. Instead, Marx saw – and was repulsed by – the misery and poverty suffered by the working class. He saw men, women, and children working twelve to sixteen hour days under intolerable factory conditions. He saw the filth and stench of the working class districts in Manchester with no sanitation of any kind – a virtual cesspool reeking of urine in which putrefied animals were left to rot and mud so deep that couldn’t walk without sinking ankle deep. And he saw the wealthy get richer as a result of exploiting – taking advantage – of the workers. Unlike most scholars of his day, Marx was unwilling to see poverty as either a natural or God-given condition of man. Instead, he viewed poverty and inequality as human made conditions fostered by private property and capitalism, the dominant economic system of the day. As Marx put it,

At the time, economists believed that the economy operated according to cold, impersonal, unchanging laws that carried men along and were beyond their control. These economists also believed that business, left to grow without government interference, would eventually produce a general benefit for all mankind. Marx set out to demythologize economics, to describe its real-world mechanics and, most forcefully, its consequences. According to Marx there are just two classes and ones membership is dependent entirely on their relation to the means of production. The bourgeoisie are those who own the tools and materials necessary for their work – the means of production such as factories and land. The proletariat or, working-class, have only their bodies and their labor as a means to produce economic goods and, as a result, have no choice but to sell their labor for a daily wage. But how was that wage determined? Marx argued that in a capitalist economic system the bourgeoisie seek to maximize their own profit and do so by exploiting or taking advantage of the working class by paying wages that barely keep them alive. As a result, Marx argued that, capitalism had within it the seeds of its own destruction. This, by the way, is an example of – in the language of functional analysis – a latent (unintended) dysfunction. Although exploiting the workers by paying low wages is intended to increase the profits of the capitalists – the manifest function of low wages and exploitation – Marx believed that it would spur the working-class to first, develop a class consciousness, and then rise to overthrow the capitalist system and establish a communist society – which was clearly not intended by the capitalists and also quite disruptive to their way of life. Although Marx’ predictions of impending revolution were never realized, his analyses of the inner workings of capitalism and the social world more generally still has much to offer. Many sociologists today agree with Marx’ belief that social conflict is at the core of society; that conflict is built into the very fabric of the social world. It is not the result of human nature or biological predispositions, nor is it the result of psychological states of mind. Rather, the way that society is structured and put together generates conflict; it is an inevitable feature of all social systems. This is so because society is made up of different social positions – such as bourgeoisie and proletariat – and attached to each position is a set of legitimate interests. According to the rules of the capitalist system owners should be interested in maximizing profits. Workers, of course, have a legitimate interest in feeding and providing shelter for their families. By virtue of the different class positions they occupy they have opposing interests and, as a result, conflict is assured. Marx’s crucial insight, from the standpoint of sociological theory, is that since society is comprised of numerous social positions, each having specific sets of interests attached to them, there is a potential for conflict whenever occupants of different social positions interact. I hope that you recognize how this Marxian notion, stripped of its political overtones, has been thoroughly incorporated into the micro-level perspective that conceptualizes – thinks about – individuals as status-occupants. Another of Marx’s major contributions was the idea that social change was continuous – and inevitable – and was rooted in the internal contradictions, antagonisms, and tensions that are built into society. Although Marx believed that the conflicts between opposing economic interests outlined above is the most important source of change, many sociologists today have broadened the scope of the conflict perspective and place equal emphasis on inequalities based on class, race, ethnicity, gender, and age. As shall be seen throughout the semester, sociologists using this perspective focus on the social causes of conflict and how differences in power and access to resources affects the manner in which these inevitable conflicts are resolved. |

Postscript: Karl Marx and Charles Dickens |

Karl Marx 1818 - 1883 |

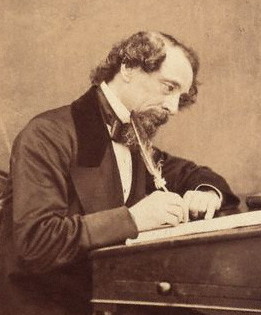

Charles Dickens 1812 - 1870 |

Marx was considered by most “decent” citizens in Europe to be a dangerous man, spreading ideas about class warfare and advocating the overthrow of existing governments. I think it instructive, however, to think about one of Marx’ contemporaries, Charles Dickens. Dickens, the author of such classics as The Adventures of Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol, Hard Times, Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities, was arguably the most popular novelist of his time. Anyone reading these, however, would know that he was a fierce critic of the treatment and impoverishment of the working classes. He portrayed, through his fiction, precisely what Marx was describing in his work. Marx, in fact, writing in 1854, included Dickens among “the present splendid brotherhood of fiction-writers in England whose graphic and eloquent pages have issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together.” George Bernard Shaw, the noted playwright, essayist, and novelist remarked that Dickens’ Great Expectations was more seditious – that is, more likely to incite rebellion against state authority – than Marx's work! And yet, the public did not vilify Dickens or consider him the monster they thought Marx to be. Why not? The answer, in part, is because Dickens did not advocate a wholesale change in the economic arrangements of the times. He doesn’t have any of his characters join a workers’ union or man the barricades in a socialist revolution . . . |

Copyright 2013, Larry Stern

All material on this webpage is for Collin College class use only. Any unauthorized duplication or distribution is prohibited.